Report: Undercover Policing Inquiry’s First Mitting Hearing

A long account of Mitting’s first hearing: legal arguments

A long account of Mitting’s first hearing: legal arguments

by Dónal O’Driscoll, Undercover Research Group

The 20th & 21st November saw the first open hearing of the Undercover Policing Inquiry before the new Chair, Sir John Mitting, who succeeded Christopher Pitchford earlier this year.

Prior to this hearing, Mitting released several ‘minded-to’ documents that indicated his intention to restrict details of undercover officers, and said he would provide an opening statement on the future conduct of the Inquiry under him. The victims of the spycop scandal approached the hearings with trepidation and scepticism.

In this long read, we unpick the hearing in detail, in particular how the new Chair is likely to approach the release of information on spycop deployments and their supervisors. We look at Mitting’s opening remarks and how he dealt with a protest. With much of the hearings focusing on ‘restriction order’ applications for spycops’ anonymity, we look at how he handled the various challenges thrown up by them.

It is worth noting how much the discussion has shifted. Arguments around releasing cover names have advanced considerably in favour of publishing, with debates now focusing on the degree to which real names should be revealed.

Nevertheless, Mitting has put down markers on the subject – his concerns are where there is a real risk to the officers or crucial factors relating to their health and expectations of anonymity. However, the stand out point is the moral right of those deceived into relationships to know real names.

Since the hearing, Mitting has handed down a number of rulings in response.

Note: this is the author’s own impressions from sitting through both days. There may be other readings / interpretations of how things went.

The opening statement

The Chair opened with a prepared statement on how he was planning to conduct the Inquiry. To a packed room at the Royal Courts of Justice, he acknowledged the work of his predecessor, Christopher Pitchford, in setting up the necessary infrastructure, legal and otherwise, to prepare for hearing evidence.

He reiterated Pitchford’s own statement and added his own support:

“The Inquiry’s priority is to discover the truth.” That is my priority. It is only by discovering the truth that I can fulfil the terms of the Inquiry. I am determined to do so.

He focused on the two key issues which led to the Inquiry being founded in the first place – the spying on the Stephen Lawrence campaign and undercover officers conducting sexual relationships with the women they spied on.

For the women targetted for relationships, he declared they were entitled to true accounts. This included the real names of the who deceived them, and which superior officers knew about, sanctioned or encouraged such behaviour – something, he noted, may require an exhaustive finding of facts. This went beyond mere legal reasoning, as he says the women have a compelling moral claim to know the full truth. This is a profound shift which impacted on subsequent matters.

Regarding the targeting of those connected to murdered teenager Stephen Lawrence – not just his family, but also his friend Duwayne Brooks – Mitting acknowledged the ongoing anguish still caused by the lack of definitive judgement on the events of 25 years ago. Evidence would be tested in public, insofar as possible, so releasing the cover names of undercovers involved essential. He also promised that more senior officers would have to answer publicly what they knew and how they used the intelligence gathered.

Finally, he noted that for a number of undercover officers, the risks to them arising from their deployments meant that if their evidence was to be heard, it would have to be done in closed hearings – at which the public and non-state core participants would be excluded.

For the Chair, this was preferable in order to ensure he did actually hear their evidence. He emphasised that in complex situations he would err towards solutions that got him to hear the evidence, an approach he demonstrated during one of the specific applications addressed later during the hearing.

Mitting then made ‘forecasts’, setting out his broad intentions. Everything being equal, the Inquiry would publish cover names of undercover officers unless there was sufficient ‘public interest’ not to, or it would cause risk to an officer. Their real names would, for the most part, be restricted. This commitment to a degree of openness was welcome, but how it played out in practice, in the face of the police’s arguments for secrecy, took up a significant proportion of the hearing’s second day.

Finally, senior officers (as opposed to the managers within the spycop units) should expect to give evidence in their real names unless there was risk to them or national security issues. Interestingly, Mitting noted that in most cases, national security issues were unlikely to arise, and arguments would mainly focus on the human rights of the officers concerned.

Mitting assured those spied upon that he shared the determination to uncover the wrongdoing and mistakes, and if that disrupted the lives of former undercovers at times, then so be it. However, as he reiterated several times over the two days, each application would be taken on its own specific facts, and nothing was fixed in stone.

What remained to be learned, then, was where he would set the thresholds of risk to an officer, and of the public interest to maintain secrecy, especially given that his minded-to notes indicated a large proportion of officers would be granted anonymity.

The protest

At this point, not an hour into the hearing, chants of ‘No Justice, No Peace’ came from the gallery, mostly populated with victims of spycops. Several people stood up and gave a direct response to Mitting’s words, expressing fully the anger of those spied upon. Dave Smith, a long standing campaigner from the Blacklist Support Group, gave a calm but passionate speech.

He spoke about how the emphasis in the Inquiry so far was meeting the needs of the police, and in this the rights of the victims were being forgotten. He spoke of how they were constantly being told to leave it to the British justice system and maintain a dignified silence, but feared they would end up with no justice at all and the Inquiry looked increasingly like an establishment cover-up.

Smith pointed at the imbalance of power, that on the benches before the Chair were eight barristers on behalf of the police and state. Meanwhile 180 core participants spied upon by police had just one barrister to speak for them and there was no funding for their individual lawyers to attend. It was a stark reminder, he declared, of the Inquiry’s structural bias in favour of those who carried out the abuse, and an issue that needed redressing.

Smith went on to reiterate the core demands of those spied upon: a complete release of all cover names of the undercover police from the political units, the names of all groups targeted, and providing core participants with their personal police files so they could see how they had been targeted.

Others added their voices. Helen Steel, a long term campaigner on this issue, rose to point out that while the police had three years to prepare so far, the victims had been given information in only the last week and it was a struggle for one person to prepare, let alone for the views of the many non-state/police core participants be brought together. It felt like if they were ‘being told to shut up and go away’, when it was in fact time to respect the rights of those abused.

After several more people had contributed, the protest concluded with further chants of ‘No Justice, No Peace’.

During this, Mitting sent for security guards, who took time to arrive and were unable to do much in any case. The protest, though determined, was peaceful and the Chair heard it out in the end. He acknowledged it, saying he understood their feelings, but if there was further disruptions like it, people would be removed. The gallery gave a collective shrug and settled down to hear the rest of his opening remarks.

Opening remarks continue

Mitting went on to address the task facing the Inquiry, noting that the amount of evidence facing him was formidable. Progress was being made on processing applications to restrict release of real and cover names of police, though much more work was still to be done. Open and closed hearings relating to officers from the Special Demonstration Squad were expected to complete by May 2018 – a two month slip on the previously revised timetable.

His hope was that restriction orders dealing with early deployments would finish soon and the Inquiry would being taking witness statements there. It would not wait for all restriction order applications being decided upon before starting on that side of things.

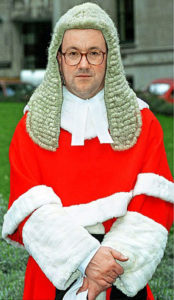

Sir John Mitting

The Chair acknowledged a concern of the core participants, saying they would not be expected to give statements until after the police had. This had previously angered non-state/police core participants (NPSCPs), as it expected them to put their personal lives into the open, while the police continued to hide – a reversal of the normal course of things.

Redaction of material, he noted, is still a major problem, with not all IT issues resolved, meaning that redactions were still being done manually in some cases. The Metropolitan Police are in charge of the processes, and Mitting seemed to be unhappy that discussions were happening on a line by line basis for the restriction orders alone, due to their excessive desire for redaction. That was not sustainable.

At this point he sent a warning shot – if the Met continued on this route, the Inquiry would take over the process. This would potentially places a greater burden on the Inquiry itself, but for the core participants, frustrated with the endless delays, it offered some hope that police intransigence was would be tackled. It seems that Mitting, though relatively new to the job, has already built up a degree of frustration with the Metropolitan Police obstruction.

Finally, Mitting seems prepared for the Inquiry to be somewhat more accessible than under the previous Chair, seeking to have more regular meetings with the lawyers of core participants who were spied up on, and having meetings with the media.

So, all in all, it was not a statement announcing a move to greater secrecy as many had feared.

Substantive matters

Next on the agenda were the two substantive issues the hearing had to deal with: the Rehabilitation of Offenders Act and a number of actual restriction orders. This was a chance to go beyond the words and get a feel for the Chair actually in action.

Over the two days, several overarching things became apparent abut Mitting. He prefers working at the level of specifics, and, unlike Pitchford, he is much more prepared to engage with the discussion in the moment. He regularly engaged with the barristers before him, whether conducting debates or clarifying his own thoughts, particularly with Phillippa Kaufmann, the lead counsel for the non-state/police core participants.

Rehabilitation of Offenders Act

The first issue addressed was that of the Rehabilitation of Offenders Act. The police are relying on past convictions of the people they spied on to illustrate why spycops were deployed and what risks the officers might face if named. However, the Act says that after set periods of time, various types of convictions are ‘spent’, and the person convicted has the right to have them ‘forgotten’. Thus, if Mitting uses ‘spent’ convictions in any of his decision-making, he has to do it in a way that does not contravene the Act or undermine its intention (and thus the rights of those people with the convictions).

How that is done is not trivial, and though a legally technical point, it is a significant one for those spied upon. Not least as they argue the spycops engineered miscarriages of justice, so the convictions being cited by police might be miscarriages of justice of their own making.

We have explained the more technical points of discussion in a previous article so will not go into depth here. Before the hearing Mitting issued a note saying spent convictions had played little role to date when reviewing anonymity applications.

He elaborated on this in the hearing, saying that in the few cases where he had considered them, it was when an individual also had unspent convictions which went to establish a pattern of behaviour. Where a person’s convictions are all spent, then he is not taking that person’s record into account.

The NPSCPs, however, had specifically wished to respond to Mitting’s minded-to. In particular, where spent convictions were being relied on, to be able to make submissions on the those convictions. Ms Kaufmann’s argument boiled down to: Mitting may order restrictions orders on the basis of convictions that themselves would be challengeable as miscarriages of justice due to the role played by undercover police in securing those convictions. This was why the NPSCPs should be able to make submissions in each case.

Another potential consequence was that if a cover name was prevented from being released because of this, then potential miscarriages of justice would be prevented from being discovered. In such a case, the Inquiry would have made effectively made a finding of fact that there was nothing to be discovered on the incomplete evidence provided by the police.

It was argued by the police, and noted by Mitting, that it would put the Inquiry in a position of finding of facts at an early stage. The police objected to this, saying it was ‘unworkable’ and would lead to mini-trials that pre-empted the substantive, evidence stage.

The Metropolitan Police’s position was also that at this stage of proceedings there was no prejudice to those whose spent convictions were being considered, and Mitting has the power to inquire if a conviction he’s being asked to consider involved the undercover officers.

Mitting’s responded, saying he was primarily interested in convictions that indicated issues of safety and harassment to undercovers, but was proceeding on a case-by-case base. The evidence phase of the Inquiry is the appropriate place to examine miscarriages of justice.

Note: Mitting has since issued a ruling on this, whereby he effectively stuck to the position set out in his minded-to. See also our earlier article on this particular point.

Restriction order applications

Then it was on to the individual applications for ‘restriction orders’, ie anonymity for officers. This being the first public hearing on this, it would give crucial insight into how the Inquiry would proceed.

Mitting was insistent that he wanted only to hear arguments on the specifics of each case, rather than general points, as considerable written submissions had already been filed. He did not get his way on this as there were outstanding matters needing addressing at a relatively high level because they affected all the applications.

In the subsequent to-and-fro complaint was made that the police were seeking to revisit previous legal discussions around openness that had been dealt with by Pitchford. The Chair said he was not having this, reiterating that the use of ‘Neither Confirm Nor Deny’ would not be a factor in the cases before him. Likewise, alleged promises of lifetime confidentiality to officers would play little part in his decisions except in specific cases.

However, care needs to be taken when applying Mitting’s words here as they applied in the main only to the handful of applications being considered at the hearing. These focused for the most part on deployments in the 1960s and 1970s.

Likewise, he noted that while ‘Neither Confirm Nor Deny’ would not play a role in his handling of these Special Demonstration Squad undercovers in the way it had been used in civil cases, it could still play a part in his consideration of later operations.

During these discussions Mitting declared he was not starting from the position that real names of undercovers shouldn’t be released, and not making presumptions on the release of officers’ real names in general. He asked of those before him – the core participants being kept in the dark about so many aspects of the heavily redacted material – to put their trust in him, saying they would accept he had to make the pragmatic decisions.

He also addressed material submitted by the police being used to justify fears by undercovers that they would be unlawfully harassed. This including witness statements from former spycops Jim Boyling and Bob Lambert. The Chair said he didn’t find this material persuasive, possibly as NPSCPs submitted a statement that shone a considerably different light on Boyling’s allegations.

Day One concluded once Ms Kaufmann finished setting out the non-state/police core participants general points on the restriction order applications.

Day Two

Restriction orders – general points

The opening of the second day saw general submissions from the other parties. Maya Sikand spoke on behalf of former undercover officer, the whistleblower Peter Francis.

She made plain that if there was a balance to be struck over releasing details of undercover officers then it needed to come down on the side of cover names being made public. Real names should be released where there was a moral right or in very limited circumstances.

Peter Francis

Sikand also warned that an eye needed to be kept on the practical consequences of releasing real names, including that it might deter some former undercovers from coming forward.

She made the point that there is a difference between senior officers and SDS managers, the latter often having been undercovers themselves. Mitting said, however, that while this might have been the situation later on, it was not so for early managers of the unit and he would handle it on a case-by-case basis.

Sikand then challenged police material on a number of inaccuracies and wrongful allegations, including what seemed to be an attempt by the police to smear Peter Francis by claiming he stood in a ‘camp’ with The Guardian and the media, with the implication he was bringing a dubious agenda. She responded it was nothing of the sort, that Peter Francis was his own person in all of this.

The over-redaction of material by police, a point of contention, had led to it needing to be specifically asked who were the experts being relied upon – whereas in the normal course of things this would automatically be disclosed.

This eventually revealed that one police expert conducting evaluations of the undercovers is psychiatrist Dr Walter Busuttil of the The Priory clinic. This led Francis to be able to reveal that The Priory was regularly used by the Metropolitan Police. Indeed, when he was pursuing his own case against the Met, he and a fellow undercover had been referred there by them, and Busuttil was co-director at the time.

When these questions had arisen, the Metropolitan Police responded with a letter saying they were upset that aspersions were being cast against Busuttil, missing the point that the potential conflict of interest should have been disclosed up front rather than having to be teased out through questions.

Following Sikand, Ben Brandon spoke on behalf of the Metropolitan Police. He accused the NPSCPs of shifting position from earlier hearings with regards revealing real names, and argued that the public interest in having the real names of undercovers and managers was only there in some cases. Revealing them was not necessary for the success of the Inquiry.

He spent much of his time countering two particular positions Ms Kaufmann had advanced to justified releasing real names. The first was that having real names could also lead to whistleblowers coming forward to reveal other incidents of sexism and racism by those officers. Mr Brandon said that such extra evidence would make the Inquiry become unmanageable.

The second was on ‘corporate police progression’, where undercovers had gone on to more senior police ranks bringing with them their knowledge of the SDS and its malfeasance. This went to the issue of policy decisions. Mr Brandon argued this was a false assumption and needed to have the allegations of wrongdoing while undercover out in the open first before examining this point. That is, before an officer’s real identity was revealed, it had to be shown that they had done something wrong in the first place.

On both points, Mitting indicated he agreed with the police barrister, though these points were of limited consequence at this stage.

Next up was Oliver Saunders, the barrister supplied by the Metropolitan Police to represent the interests of undercovers and their managers – the ‘Designated Lawyers’ team. This is a role distinct from the Metropolitan Police as an organisation, which has its own representation – Mr Brandon, mentioned above. It is this sort of proliferation of legal representation for police that has considerably upset NPSCPs.

Mitting who wanted to know of Mr Saunders why his submissions had sought to re-open the discussions on openness which Pitchford had dealt with. He replied that the Designated Lawyers had not been in place at the time those arguments were being heard, and that regardless, some weight still had to be given to promises of confidentiality as it fed into wider aspects such as expectations in the right to privacy.

The Chair accepted this to the extent that the effect of promises of confidentiality would play some role in his decision-making. While saying this, he did acknowledge that he was not swayed by Ms Kaufmann’s argument that matters of risk should only consider physical and psychological harm, but consider it all on a case-by-case basis.

Mr Saunders elaborated on the point, arguing that officers had made choices when undertaking undercover work which had significant impacts on their lives, including building it around the need for some secrecy. There was also a mutual expectation of the state – the undercover will not talk about their deployment, and the state will not expose it. Having constructed their life around this, it then exercised their Article 8 rights to privacy. He claimed it would be wrong to change this, especially where there was no existing allegations of wrongdoing.

Mr Saunders also addressed the impact on the state’s ability to recruit further undercovers, a matter returned to at the end when it was addressed by Counsel to the Inquiry, David Barr (see below).

Individual restriction order applications

Only once the general points had been made was it possible to move on to consideration of the individual restriction order applications over the real and cover names of undercover officers, who are known by code numbers beginning ‘HN’.

There was considerable frustration by the non-state/police representatives, who were fighting their corner with one hand tied behind their backs given the amount of material that had been redacted and not even gisted. Indeed, in some cases they could make no substantive points, though Mitting was occasionally able to provide in general terms the types of reasons prominent in his decision-making.

This first tranche of officers were all Special Demonstration Squad, either from the early days of the unit in the 1960s and 1970s, or connected to the spying on the Stephen Lawrence campaign.

HN16

First up was HN16. In this case restriction on real and cover name were sought due to sensitivity of the deployment. Mitting was concerned about the risk to N16’s current employment, and wanted to deal with both cover and real name together. This was opposed by the NPSCPs who said the cover name could still be disclosed. The police responded saying it was better to make complete decisions rather than bit by bit. Mitting replied that ideally all decisions regarding restriction orders for a particular officer would be made at once, but that was subject to provisos and all decisions were subject to review – a real possibility in this case of HN16.

-

Mitting has subsequently ruled that HN16’s cover name will released but not his real name.

HN58

HN58 is not only a former undercover, but also a leading SDS manager at the time of the spying on the Lawrences. The issue here was whether both the cover and real name should be revealed given the different positions he had held within the SDS. This meant resolving the tension between revealing the names of managers who had overseen spying on the Lawrences, and cover names in case there were earlier relationships or miscarriages of justice that needed to come to light.

The initial discussion revolved around the point of releasing cover names into the public in the first place. Jonathan Hall, for the Met, argued that the Inquiry shouldn’t disclose simply on the chance that something might turn up; that closed hearings should be treated as being of value and did not shut down the effectiveness of the Inquiry as the Chair was in a position to test material.

Mitting responded that his predecessor had rightly rejected a closed Inquiry and needed to look at individual officers. He also reiterated that if material on relationships were to come out then real names had to be released.

Hall continued to object, saying it was dangerous to release all cover names on the off-chance of revealing a relationship, and that some information may never come to light. The Chair partially agreed here, saying that the Lawrence issue was more important than a potential undercover one.

Ms Sikand said that Peter Francis believed that if it came down to it, then the choice should be to release the cover name in the first instance, but senior officers needed to account for their decisions. Hence, there was an additional public interest in the real identify being revealed.

She also pointed out that the risk assessment put the threat to N58 as low, something Peter Francis agreed with. Mitting answered that saying it was not possible to resolve in open hearing, but the tension between the principles he had set out would require a closed hearing. He told Ms Kaufmann that the NPSCPs could not know if there was no significant risk to N58, but that though the risk assessments were helpful, they were not determining his views.

-

Mitting has subsequently ruled that there will have to be a closed hearing to determine his how he would rule on HN58.

HN68

Next was HN68, deceased, who had been a manager as well as an undercover. The argument here focused on the rights of his widow who had concerns over her husband’s name being revealed. Again the police returned to confidentiality issues, that the Inquiry could proceed without the real name and it would be unfair to cause the widow upset on speculative grounds. Mitting noted that as N68 was dead, he couldn’t be called on to account for his actions in any case so revealing his real name would not be particularly helpful. The Inquiry could rely on his personnel records if needed.

-

Mitting has subsequently ruled that HN68’s cover name will released but not his real name.

HN81

This was followed by HN81, a key officer given his role in spying on the campaigns around Stephen Lawrence’s murder. Mitting made it clear that what was in his mind was not the physical risk to the undercover, but the state of his mental health. Ms Kaufmann complained that this has not been sufficiently revealed, to which the Chair said it had been explored in a previous closed hearing including ways to mitigate the risk. Ms Kaufmann asked that the release of the real name was kept under review, but was rebuffed on the grounds that even saying this may exacerbate N81’s issues.

It was conceded by the Metropolitan Police that the cover name needed to come out. They would not seek to protect their own interest in this, but maintained HN81’s real name should not be revealed.

Mitting took the position that the cover name and the group targeted would be revealed, but time would be given to HN81 to prepare for this. He subsequently ruled to this effect.

HN104

Following HN81 was HN104, better known as Carlo Neri. This was a whole different type of discussion as the real name is actually known to many of those he spied upon. The point put to the Inquiry by the NPSCPs was that the real name needed to come out – basically, if you don’t do it, it will be done in any case. Ms Kaufmann maintained the point that though the family of HN104 had its own interests, HN104 had multiple relationships with those he targeted and there was a strong interest in accountability.

Mitting stated that he respected and commended the decision to not make his real name public to date, but asked if there could be cooperation on managing the revealing of the real name. Ms Kaufmann indicated yes, but had to take further instruction. Mr Hall asked for a closed hearing on the matter.

HN123

HN123 is another Lawrence-connected case where it was being proposed to restrict real and cover name. Mitting said that though all the material was not public this was quite an unusual and difficult case, based on the mental health issues of the officer (apparently not connected to their deployment), and that if the cover name was released publicly it might hamper the Inquiry’s ability to get HN123’s evidence, something Mitting was keen to ensure he had.

It was notable, in this application, how little weight the Chair appeared to be giving to the police’s risk assessments of officers.

There did seem to be a question as to how much this applied to the Lawrence aspect, though Ms Sikand, on behalf of Peter Francis, explicitly said that the group HN123 targeted did interact with the Lawrences, and thus the cover name was needed.

-

Mitting has subsequently ruled that neither HN123’s real or cover name will released on the grounds of HN123’s ill health, and that he appears to be only indirectly connected to the spying on the Lawrences, despite the evidence of Peter Francis to the contrary. This ruling will be revised if new facts emerged.

From here, the applications moved on to a tranche of older undercovers who had been deployed in 1960s and 1970s. Mitting was quite dismissive of this, saying that too much energy was being expended on what was ‘ancient history’ as they would not assist in learning what went wrong with the SDS. He wanted to know why elderly spouses couldn’t be left in peace.

HN297

This changed somewhat when the application over the real name of ‘Rick Gibson’ (HN297) came up. There was a bombshell in court when Kaufmann was revealed ’Gibson’ had a number of sexual relationships, something otherwise seemingly unknown to either Mitting or the police’s lawyers. The Chair noted that this changed things considerably, and was in the period when it was suspected that bad practice in the unit was becoming routine.

For him, publishing the real name became a matter of timing and further information was needed with regards to the women targeted who he wanted statements from if possible, including if they needed to be told privately first. The interests in not publishing the real name did not counter their right to know, but he wanted to learn more as this was information that had just come to light. As a result, a decision would be postponed.

HN321

HN321 offered another challenge. This undercover was abroad and threatening not to return if his real identify was revealed.

The police ran several arguments here. They focused on the fact that, as yet, no wrongdoing was being alleged and therefore expectations of privacy were that much greater. Mr Hall addressed the point that real names were being sought in order to confront the officers. He argued that all the officers were being tainted together, and this was wrong as the entire barrel was not rotten, the desire to confront should not be in the mix. Mitting responded that they just have to put up with it, and that it was not always confrontation that was being referred to, but unwelcome attention, something quite different.

-

Mitting has ruled that HN321’s cover name will released but not his real name.

For HN321 and other undercovers, the police made an elaborate point that the officers had built their lives around the need for secrecy on this aspects of their lives and with that went to the need to respect issues of confidentiality and Article 8 (the right to private and family life), and so the disruption from the breaking of that confidentiality and how they’d shaped their lives was a violation the right to private life. The Chair responded that secrecy itself was attractive and could give something importance it would not otherwise have.

HN333

The final application of note was HN333, which was not much covered in the hearing, but was notable in that both cover and real name were to be restricted, despite the low risk – in part on grounds of the officer’s subsequent career and reputation, though what this was has not been elaborated on. In his ruling, Mitting also relied on the expectation of confidentiality. It is hard to say more on such incomplete material, but this case stands out for the quite different tack that Mitting took here and the keenness he showed to protect a particular person’s reputation.

The other applications were dealt with in a pro forma fashion, partly out of desire to complete the full hearing within a day rather than run into a third one. This left only a few outstanding issues.

-

In his Ruling of 5 December 2017, Mitting has given restriction orders over the real names of nine undercover officers considered during the hearing, but said their cover names will be released where they are known (some were previously released). For two undercovers, HN123 and HN333, their cover names will also be restricted. The cases of ‘Carlo Neri’ and ‘Rick Gibson’, and HN58 require further hearings and evidence before a final ruling made.

Deterring recruitment of new undercovers

Counsel to the Inquiry, David Barr, addressed the statement of Chief Constable Alan Pughsley, the national lead on undercover policing, which had been submitted by the police as part of their evidence. Pughsley was arguing that the Inquiry itself and its openness was deterring applications by police officers to undergo training as undercovers. In this, Pughsley sought to reinforce a point made by a police officer known only by the cypher: ‘Cairo’ – who had previously submitted generic evidence on the risks to ex-undercovers and undercover policing in general.

Barr noted that Cairo had also noted there were alternative reasons why this might be the case but there was not enough to go on. So, to attempt to answer this, the Inquiry had released part of a statement from Louise Meade, who oversaw the recruiting process for undercover training at the College of Policing. She had noted that a great deal of change in the recruiting process had taken place, with a focus on getting the most suitable officers, and that there was no statistical basis to support Pughsley’s assertions.

There then followed an exchange between Mitting and Mr Hall for the Metropolitan Police. The Chair said that Pughsley and Cairo’s thoughts on the matter were not influencing his approach, that he had to get to the truth and if that deterred new officers then so be it. Mr Hall responded, saying undercover work was needed and the Inquiry needed to consider its effect on recruitment and retention. Mitting stated that he would not pull his punches based on future deployments.

Mr Hall came back saying that a possibility of an allegation being made was all it took for there to be a deterring fear, which counted for a lot at this stage. Mitting dismissed this, calling it speculation as the position was not that clear cut. Hall concluded weakly that Cairo should be treated as authoritative on this point.

Helen Steel

Helen Steel at the Royal Courts of Justice

The last remarks of the hearing went to Helen Steel, representing herself as a core participant. She addressed the general evidence, noting how it presented the victims of the spycops was insulting and added to their pain.

She pointed out in Pughsley’s statement how her search for the truth was listed under ‘harm to individuals’ (i.e. undercovers), without acknowledging the background to why she had spent years trying to track down the man who had invaded her life. It was insulting to read about the ‘poor police’ when they had left such damage in their wake.

She put into context that, while the undercovers were putting forward mental health issues as a reason for privacy, they were trained in precisely such tactics, in that many had used feigned breakdowns as part of their exit strategies.

Steel also noted that there were many inaccuracies and lies in the generic statements. Additionally, she asserted that the excessive redactions, where they talked of core participants such as herself, all fed into the ongoing sense of personal invasion. The delays caused by the redactions and applications were part of the general imbalance where by the police held the power even though the Inquiry was into those same police, and this only impacted further on their victims’ own mental wellbeing.

Her final points addressed the need for the list of groups spied upon to be released immediately. The spycops units that were not involved in criminal policing, but political policing. It is vital for all that it is made clear who was being spied upon and why. The list of groups is known, it is already sanitised of material relating to actual deployments, so there is no reason to not release it.

Conclusion

A long two days with a substantive amount of material and points raised and discussed. If a point was to be taken from it, is that Mitting’s sparse minded-to notes indicate not that he has ignored a bunch of the arguments and material, but that he is discarding much of it as not impacting on his decision making process, and this includes the police’s risk assessments.

For now, much of his concern is on mental health issues and intrusion on elderly family members. This is likely to change for officers of more recent periods.

Related documents:

-

Mitting’s ruling on Rehabilitation of Offenders Act & press notice

-

Mitting’s Minded-To of 3 August 2017 and Supplementary Minded-To of 23 October 2017

-

The Undercover Research Group has been assembling what is know about each individual officer and the status of their restriction order applications. This can be found at powerbase.info/index.php/N_officers

Dónal O’Driscoll from the

Dónal O’Driscoll from the  The announcement of the terms of reference for HM Inspectorate of Constabulary in Scotland’s review into undercover policing manages to go beyond being meaningless, insulting those demanding answers for historical abuses by spycops, explains Dónal O’Driscoll

The announcement of the terms of reference for HM Inspectorate of Constabulary in Scotland’s review into undercover policing manages to go beyond being meaningless, insulting those demanding answers for historical abuses by spycops, explains Dónal O’Driscoll