UCPI Daily Report, 26 April 2021

Tranche 1, Phase 2, Day 4

26 April 2021

Evidence from witnesses:

Diane Langford

Dr Norman Temple

After last week’s opening statements in this new round of Undercover Policing Inquiry hearings examining 1973-82, today was the first day of witnesses giving evidence.

Before it started there were protests outside the Inquiry venue, with blacklisted workers and other spied-on activists demanding their secret police files. It was joined by the roving poster van from Police Spies Out of Lives that had visited the Royal Courts of Justice, the men-only Garrick Club where Inquiry Chair is a member, and New Scotland Yard.

Diane Langford

Diane Langford was questioned by Kate Wilkinson by behalf of the Inquiry.

Diane Langford, New York City, 1996 [pic: Marion Macalpine]

By 1968 she was a volunteer at the Campaign Against Racial Discrimination, and had joined NATSOPA, the print union. By the end of that year, she had played an active part in the protests against the Vietnam War. She was part of a group called the Britain-Vietnam Solidarity Front (BVSF).

Langford said that her main focus over the past 50 years has been the liberation of women from all forms of oppression and exploitation. She worked politically with Abhimanyu Manchanda, who she later married.

THE SPYING BEGINS

The Special Demonstration Squad were reporting on her and Manchanda by March 1969 [MPS-0732690]. That early report – a BVSF weekly meeting – calls gives Manchanda’s first name as Al. Other reports call him Albert. He was never known by these names.

As well as personal names, Langford disabused the Inquiry of the name for their politics at the time:

‘We didn’t call ourselves Maoists, we called ourselves Marxist-Leninists.’

Although, with her tongue-in-cheek, she said she was happy with ‘Maoist’ as it was shorter!

She and Manchanda saw a need for (and likelihood of) anti-imperialist revolution elsewhere in the world. They saw the various struggles in different places as the same battle for freedom -from imperialism and oppression. There is a spycop file [MPS-0736447] of a 1969 speech by Manchanda that refers to:

‘the world front of imperialism which must be opposed by a common front of the revolutionary movement in all countries’

Langford said that, while there seems to be some investigation into the propensity for violence for spied-upon groups, it can be seen from the other direction; these are people trying to resist the violence of the State in order to get justice and liberation.

Whilst there were politicians such as Enoch Powell espousing overt racism, they also saw all the parties of the British government as wilfully oppressive, enforcing a racist unjust system that divides the working class and diverts wrath away from the ruling class.

These struggles against injustice continue, as we see in everything from deaths in custody and the campaigns that respond to them, to the continuing struggle for women’s liberation:

‘I still think that the State is a force which is there to act as the enforcer of oppression, yes.’

COLLECTIVE IMPERATIVE

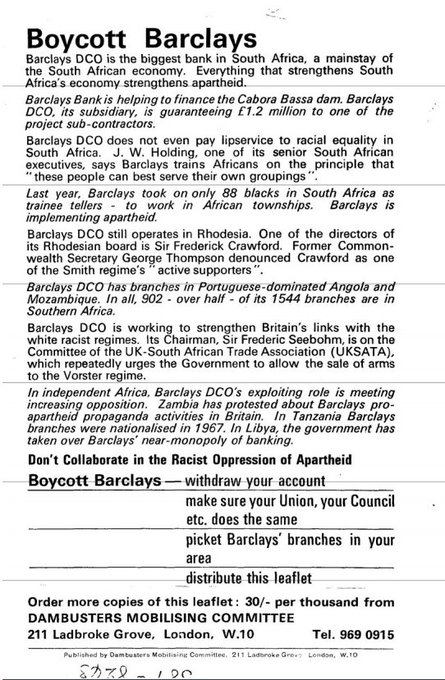

Langford was asked what methods she and her comrades used to achieve these ends. She listed many examples including demonstrations, public meetings, trade union activity, industrial activity, literature, film screenings, rent strikes, boycotts, occupations, street theatre – even parliamentary lobbying.

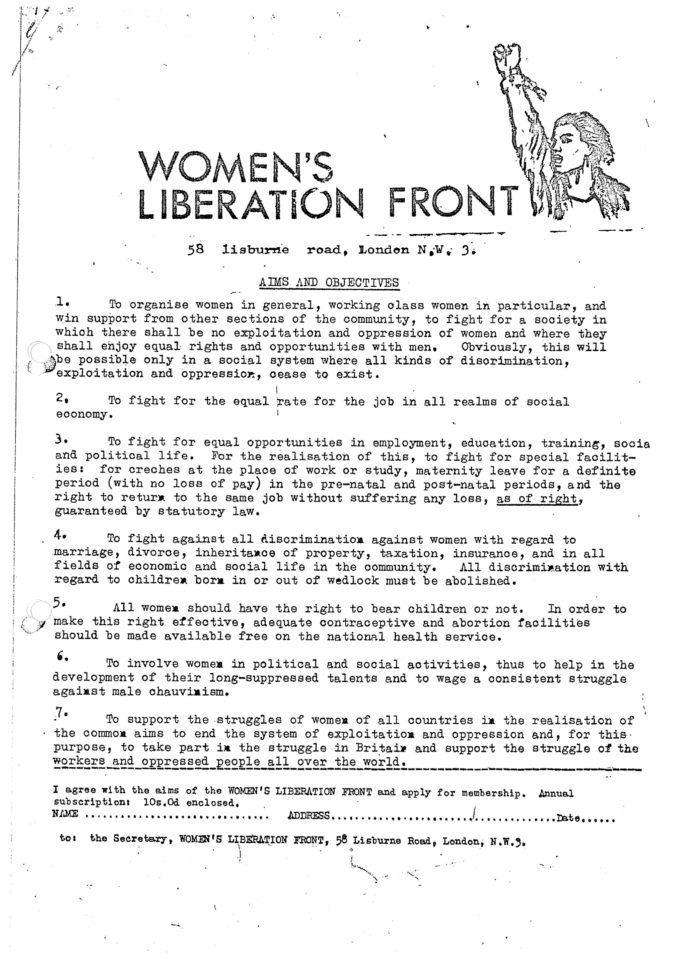

The Women’s Liberation Front’s 7-point mission statement, 1971

Recalling the way that her group operated, Langford explained that they believed in taking collective action, not acting as ‘individualist idiots’. They frowned on certain activists’ methods, including ‘anyone who indulged in macho posturing’. She cited one guy taking off his shirt outside the South African embassy and setting fire to it – he was later condemned by the group for this ‘Petit-bourgeois adventurism’.

She explained some of the differences between her group and the Trotskyists, for example the Trotskyists did not see the struggle in Vietnam as sufficiently revolutionary, as these subsistence farmers were technically landowners.

They also rejected the politics of the Soviet Union, which had occupied Czechoslovakia, and appeared to them as another form of imperialist project.

Whilst they subscribed to Lenin’s idea of the dictatorship of the proletariat as the ‘magic weapon’ to guarantee victory, and adhered to the principle of revolution by violence, smashing the old state and seizing power by force, they saw these were very distant possibilities.

By definition, they required mass support before conditions could approach being right and, citing Lenin’s comments on the British aversion to revolutionary ideas, she said there was no UK mass movement ready for revolution. Manchanda was not convinced that sections of the white working class were ready to give up the privileges they had received as a result of colonialism.

WOMEN’S LIBERATION FRONT

She confirmed that her feminism stemmed from this same global anti-imperialist thinking.

In 1970 she founded the Women’s Liberation Front (WLF).

Some of the groups Langford belonged to in were targeted by ‘David Robertson’ (HN45, 1971-73). One of his earliest reports is dated 16 February 1971 [UCPI0000010570], and includes a leaflet detailing the WLF’s main aims.

Many of the aims including equal pay, equal opportunities, childcare facilities, and birth control are now accepted across the political spectrum (if not always implemented).

SPYING ON SMALL INNER-CIRCLE GROUPS

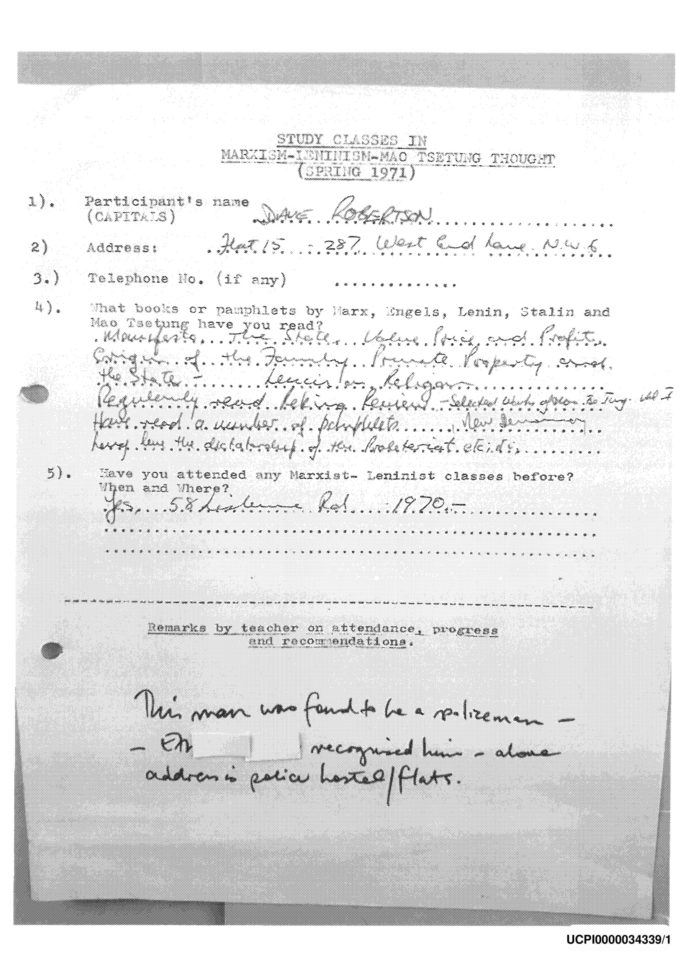

Spycop Dave Robertson’s application for study classes in Marxist-Leninist Mao Tsetung thought 1971

Langford and Manchanda formed the Revolutionary Marxist-Leninist League (RMLL), a group of around ten people with a focus on studying deep political theory. They sought to influence and lead the work of groups such as the WLF, BVSF and Friends of China. They regularly met at Langford’s house.

The Inquiry was shown another report by ‘David Robertson’, this time concerning an RMLL meeting in January 1971 [UCPI0000010567]. For the Inquiry, Wilkinson noted that this meeting lasted three and a half hours and asked if this was a standard length of meeting for this group?

With a weary note in her voice, Langford replied, ‘I’m afraid so, yes’.

This particular meeting was attended by 14 people. Three members were applying for jobs at Fords in Dagenham. The WLF, in the meantime, was planning to send its members to get jobs at the Metal Box Company. This was, Langford explained, a deliberate strategy to work at places where they may be industrial action, although their role was not to impose – again, their overarching principle of collective action came first.

Robertson was said to have attended many such meetings at Langford’s home. She seemed unable to accept he had been invited to these closed meetings despite the level of detail in the reports:

‘I find it very hard to believe that he was actually in the room, as he would not have been a member of that inner group. I should explain that we had a system of candidate membership and so there may have been someone in the room who was a candidate member’

She offers a alternative source for the intelligence – perhaps the room was bugged, or if there were some disgruntled group members (who were being challenged over their misogyny) who might have gossiped to a sympathetic person in the pub.

Robertson filled out a form for Langford [UCPI 00000334339], applying to join group’s Marxist-Leninist Mao Tsetung thought study classes in the spring of 1971.

Robertson was Scottish, and Langford remembers talking with him about the political situation in Scotland and noticing that he seemed quite clueless about past struggles such as the Upper Clyde Shipbuilders.

WOMEN’S GROUP GETS A WOMAN SPYCOP

The SDS sent ‘Sandra Davies’ (HN348) to infiltrate the WLF. She has told the Inquiry:

‘Women’s liberation was viewed as a worrying trend at the time.’

Despite having the same responsibilities as her male colleagues, because Davies was a woman she was only paid 90% of a male wage, in accordance with police policy at the time. Ironically, she received this partial wage in order to undermine a group campaigning for equal pay for women.

Davies reported on the WLF’s study group in March 1971 [UCPI0000026992]. This was a meeting at someone’s home, attended by Davies and just six other women. Langford pronounced this to be:

‘very very strange indeed… she would have had to do a lot of work to ingratiate herself to get invited to a meeting like that… she went from a public meeting to private meetings in a very short while’

OUSTING MANCHANDA

Another Robertson report [UCPI0000011741], from March 1971, details an extraordinary meeting of the RMLL that went on for 9 hours. It’s a very detailed report. The 17 people attending this meeting were expected to prepare, and write a paper in advance.

The meeting had been called in an attempt to resolve differences which had emerged in the group, but which caused its eventual split. In the report, Roberston characterised it with brazen contempt for Manchanda:

‘The object of the meeting was, in fact, to “cut down to size” the organisation’s leading personality A MANCHANDA whose offensive manner, dogmatic attitude, bullying techniques and general inefficiency have become too much even for his admirers to swallow.’

This was not the first sneering disparagement from Robertson, who’d previously reported on Manchanda’s ‘insufferable anecdotes’ about his baby, and criticised him for doing childcare while Langford went out to work.

There are a lot of details of private matters at a private home. Robertson claimed he babysat the couple’s infant child. Langford was aghast:

‘I find it absolutely outrageous that he would even make such a suggestion… we would never have left a young baby with someone we hardly knew – certainly not!’

Langford condemned his report as highly subjective and was baffled that this sort of thing was shared with MI5:

‘It’s not even about our politics, it’s about our personal lives, and it’s so intrusive, so nasty and so petty… How did these things end up in the reports of a supposedly serious operation?’

Langford said one of the reasons for the meeting was that many women on the left were starting to examine and call out ‘various misdemeanours’ by left-wing men. The report mentions a letter one of the group had sent to Manchanda. Robertson described it as:

‘a very personal attack on the private morals of [name redacted] arising from an incident that had taken place some time previously’

Langford said that it was much more serious than that. It was an accusation of attempted rape against a man in the group. She remembers the man denying it and his exact words, ‘she’s too ugly to rape’ are still ‘burned into my memory’.

More to the point, Roberston was a police officer hearing a report of a serious offence, yet his response was to misreport in such vague terms that none of his police colleagues would be aware of the truth.

Langford was asked if anyone else in the group reported it to the police:

‘Very few women would. We all knew we’d be subjected to further humiliation.’

The meeting had heated exchanges and Manchanda was suspended from the RMLL. It means Robertson, or whoever the informer was, must have contributed to the meeting and had a vote. Robertson noted this probably meant that Friends of China and the Britain-Vietnam Solidarity Front would be disbanded too.

DEMOLISHING THE WOMEN’S LIBERATION FRONT

Six-months later, in September 1971, there is a report [UCPI0000027021] from a WLF meeting where an emergency resolution was passed to expel Diane Langford from the group that she had set up. The vote was unanimous – so Sandra Davies approved and voted Langford out as well.

According to one of Davies’ reports [UCPI0000010932], the Black Unity and Freedom Party was planning a children’s Christmas party in 1971, and they asked the WLF to contribute home-made sweets and cakes.

Asked why the intention to bake was worthy of reporting by police charged with preventing disorder, Davies seemed to suggest it was a ruse to indoctrinate kids:

‘They were involving themselves with children and the sweets and cakes were an addition. They wanted to get their philosophy across to as many groups as they could. That was their aim’

Another of Davies’ reports [UCPI0000010907] mentions a jumble sale being organised by the WLF. Again, she defended this because:

‘they would have used it as another opportunity for advertising their aims’

Both of these reports were copied to MI5.

In February 1972, a report [UCPI0000010908] shows that spycop Sandra Davies had been elected WLF treasurer. A month later, Davies reported [UCPI0000010911] on an emergency meeting of the Executive Committee of the Revolutionary Women’s Union – as the WLF was now called – that decided to suspend three members from the wider group for ‘disruptive behaviour’.

Six weeks after that, on 4 May 1972, Davies attended another Women’s Revolutionary Union meeting at a member’s home. According to her report [UCPI0000010913], it opened with comments about a general lack of enthusiasm within the group, older members dropping out and not being replaced by new ones. The organisation was finished.

NIXON PROTEST

In January 1973, a report [UCPI0000010247] concerns a private meeting of the Britain-Vietnam Solidarity Front to organise a protest coinciding with the inauguration of US President Richard Nixon. Although much of the world saw Nixon as improving relations with China, the BVSF were keen to protest against Nixon’s extension of the Vietnam War into Cambodia and Laos.

Robertson and Jill Mosdell (HN346) are both shown as contributing to this report. Langford noticed the name Digby Jacks, NUS president at the time, and believes this meeting was about organising the practicalities of the march they were organising. She made the point that they would communicate with the (uniformed) police to agree the route of any marches.

BURNING BANNER BOOKS

Banner Books is mentioned in a report from 1972. It seems that Robertson was working there. In her opening statement last week, Langford pointed out that this meant the SDS had keys for the shop. She remembered that it was later burned down by fascists. This hadn’t appeared in any of the police reports.

For the Inquiry, Wilkinson promised that Robertson will be asked about this when he gives evidence on the morning of Tuesday 27 April.

Ultimately though, Robertson’s cover identity was compromised in 1973 and his deployment ended. If, as Wilkinson suggested, the fire occurred in 1975, this might be the reason he didn’t mention it.

THE MASK SLIPS

In 2015, Langford said that Robertson had long made them uneasy:

‘A moustachioed Scottish man, Dave Robertson, aroused suspicion because he was always driving a different car. When challenged he claimed to be working for a car rental firm. On another occasion he’d told me he worked at a club called the Tatty Bogle. One of the comrades went down to check it out and found this to be untrue.

‘At Manu [Manchanda]’s suggestion, we didn’t confront Dave, but assigned him the most onerous tasks: collecting heavy banners and placards in his car and carrying them on marches. He was always called upon to buy everyone drinks and asked to memorise long passages from James Maxton, an obscure Scottish Marxist.

‘The funny thing was, I quite liked Dave. He was always good-natured and went along with the aggravation. Then all that changed. The sinister nature of his work revealed itself.’

Langford inadvertently played a key role in the blowing of Robertson’s cover. She was working at the Daily Mirror and brought a co-worker, Ethel, along to a meeting of the Indo-China Solidarity Committee about President Nixon’s bombing of Cambodia.

Robertson walked in and Ethel greeted him brightly. He came over very quickly – acting ‘like overbearing men often do’, said Langford – grabbed Ethel by the wrist and said, ‘I want to talk to you outside.’ They didn’t come back.

For about a week, Ethel was awkward with Langford and wouldn’t talk about it. Eventually, she told Langford that she knew him from living in a nearby flat, and it was well known his flat was a police flat.

Ethel explained:

‘Dave works for the Special Branch. He’s threatened that if I tell you or Manchanda, he’ll cause something nasty to happen to my family in Ireland.’

Robertson was never seen again. He and the two officers deployed alongside him, Jill Mosdell and Sandra Davies, were all withdrawn at the same time.

Despite serving in the Met’s elite subversion and public order unit for two years, Davies said in her witness statement to the Inquiry:

‘I did not witness or participate in any public disorder whilst serving with the SDS. I do not even recall going on any marches or demonstrations. I did not witness nor was I involved in any violence.’

It must have been obvious very early on in her deployment what she was involved with. And yet, she was still there, spying full-time on that group, two years later. Looking back, she continued:

‘I do not think my work really yielded any good intelligence, but I eliminated the Women’s Liberation Front from public order concerns’

LEGACY

Langford says the truth has left her feeling guilty for being unknowingly allowing Robertson into their political groups. She feels anxious about the possibility of State reprisals on Ethel, and outraged that a woman she trusted violated her family space when they were just trying to improve the lives of women.

Langford flatly rejects the police lawyers’ exhortations to make allowances for bigotry in the reports as merely ‘the standards of the time’. She sternly asserted that there was no excuse for such sickening racist, sexist and homophobic language and attitudes. The Universal Declaration of Human Rights had been declared a generation earlier. There were any number of people like Martin Luther King, Claudia Jones, and James Baldwin who were alive and not bigoted and very publicly saying so. Such prejudice and oppression was no more right or acceptable then than it is now.

The Inquiry has uploaded Diane Langford‘s account of her political life, ‘The Manchanda Connection – a political memoir by Diane Langford‘

Witness statement of Diane Langford

Dr Norman Temple

Dr Norman Temple was Zoomed in from Vancouver (where it was 8.30am when he started). He was, as everybody agreed (even Counsel to the Inquiry David Barr QC who we ran into leaving the venue and who did his questioning), ‘quite a character’.

Temple attended university in Liverpool from 1965-67, but didn’t study much. He was a member of the Labour Party. His interest was piqued by a periodical from China and after he moved to London he got involved with Maoists there.

In 1967, the Vietnam war intensified. The civil rights movement, the hippies in San Francisco, the women’s movement, the gay rights movement were all running in parallel. In Britain there was the specific political situation in Northern Ireland, in France there were the événements of 1968.

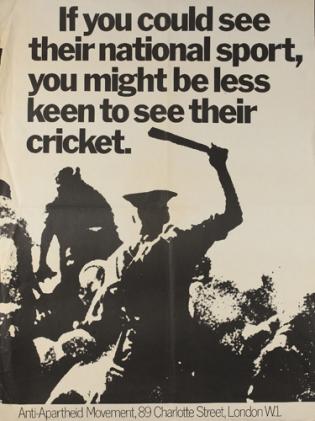

He pointed out that there was lots of overlap between these different campaigns, and others, including the fight against apartheid.

He saw that these issues were all connected, and that the system was the problem.

He saw three main factions on the Left at the time: those who were pro-Soviet Union, those who were pro-China, and those who were Trotskyists. He was drawn to the pro-China people, the Maoists, and happily described himself as ‘rent a mob’ – ‘a floating revolutionary’ who got involved in lots of things.

Most of the hearing revolved around the politics of the (splinter-)groups he had been involved in, and it turned out Temple still had quite strong opinions about his former comrades.

PALESTINIAN SOLIDARITY CAMPAIGN

Palestine ‘burst on the scene’ in 1969 and became an issue internationally, like apartheid and Vietnam. The Palestine Solidarity Campaign (PSC) was formed at the Egyptian Embassy, near to the old MI5 building in Mayfair. Asked about his membership of the ‘Kensington and Paddington branch of the PSC’, Temple retorted that ‘It would be more accurate to say I was the branch’.

We were shown an SDS report dated 17 June 1970 [MPS-0739227] signed off by a Detective Inspector (HN294, 1968-69), which includes personal details about members of the group, including their addresses, phone numbers, employment, etc.

Temple said he had no idea that the police were taking such an interest in his doings. He guessed that their thinking was ‘we better find out what these people are are up to case they do something a bit naughty’ – a precaution, just like smoke detectors. Which somehow made it sound like he was giving evidence for the police.

There were about 20 branches of the PSC in the UK, and ten affiliated organisations.

These included Arab student groups, the BVSF and CPGML (Maoist), International Socialists (Trotskists), etc. At a joint conference on 6 February 1971, the Maoists tried to take control of the PSC, but weren’t supported by the Arab student groups. The Trots were trying to do much the same thing.

IRISH NATIONAL LIBERATION SOLIDARITY FRONT

Temple then was asked about his involvement in the Irish National Liberation Solidarity Front (INLSF) in September 1970. It was run by an internal organising committee, which Temple was invited to join after 2 or 3 weeks. The group was producing a paper and needed all the help they could get.

Asked how security-conscious the INLSF was, Temple suggested that for a revolutionary organisation, being considered so insignificant by the police that you’re not under surveillance is ‘the ultimate insult’. The main thing the group did was to remove the telephone from the room during meetings, because they assumed all of their phones were tapped.

The principal activity of the INLSF was the production and distribution of the Irish Liberation Press, a newspaper which was sold in Irish pubs and venues around London. The newspaper dominated everything, according to Temple. They spent a lot of time producing it and then distributing it.

Undercover officer ‘Alex Sloan‘ (HN347, 1971), who infiltrated this group, was around for approximately four months at the start of 1971. According to Temple, he would have visited the flat where the paper was made, but he never got to the level of being trusted enough to be invited to meetings of the inner group.

The Inquiry was treated to a picture of an issue of the newspaper, while David Barr QC read the rabble-rousing text out loud.

Temple described the piece in the paper as ‘full of all these cliches’ and ‘very colourful language’, and did not necessarily reflect his views on things: ‘Everything there is written by Davoren’; nobody else was ever invited to write an article, they might be assigned ‘sort of chicken feed’ tasks.

Temple really sounded as if he still had an axe to grind with Davoren. The latter was the ‘Editor’ of the paper, but also ‘the author of everything’, and someone who believed they never made mistakes, says Temple.

Asked to talk about the level of disruption caused by the INLSF, Temple spoke about the Hyde Park demo, which he probably missed (as he and four others had gone to a trip to Ireland over Easter 1971). INLSF demos would attract 200-300 people, and their pickets around ten.

David Barr questioned him about different tactics used by the group – Temple confirmed that these included putting up posters, and what could maybe loosely be classed as ‘political education’. They would focus on the issues pertinent to people in Ireland, rather than providing a traditional Maoist political education.

Davoren, however, had his own personal political ideology. He ‘loved Stalin’ and wrote about him in the paper, but ‘nothing ever on Chairman Mao’, so Temple thinks it would be more accurate to describe him as a ‘Stalinist’ than a ‘Maoist’.

The Black Unity and Freedom Party, a Black organisation based in Finsbury Park and South London, was ‘the only other organisation that we were friendly with’ – there was no ideological disagreement between the two groups as they worked on completely different issues.

A next report [MPS-0739488] mentions a visit that Davoren paid to the ‘Chinese Legation’ in April – Temple was ‘totally unaware of it’ but reckons this is the sort of thing that Davoren may have done.

The trip to Ireland, mentioned above, was aimed at selling lots of papers, but border control noticed the thousands of copies in their van and wouldn’t let them bring their propaganda onto the ferry.

At a meeting of the group afterwards, according to the report that ‘Sloan’ submitted, there was ‘comment and disbelief’ about the statement of support of the Provisional IRA, who allowed the paper to be sold on their territory.

(Before this support was confirmed, there was an incident Belfast, when the INLSF paper-sellers were told ‘you have five minutes to get out’.) The only topic that Temple felt was safe to debate in NI was the Palestinian struggle.

Davoren was very critical of the IRA and its bombing campaign – he denounced them as ‘Catholic nationalists’. He did not think of them as a left-wing organisation, but people with politics different to his. Asked if Temple had met with any Protestant groups, Temple said ‘absolutely not, that would be very bad for the health'(!)

The hearing then moved to details about dates.

The organisation split after that meeting, with roughly half of the group walking out.

Temple stayed on for some time and shortly afterwards, Davoren set up a new organisation: the Communist Workers League. They were sent out in pairs to sell the paper. There must be mistakes in the reports, Temple says, the CWL can’t have been mentioned before the split.

He doesn’t think he was ever paired up with ‘Sloan’ and doesn’t remember having any proper conversation with the guy. He said that there was another member named Jackson who several of them believed to be a spycop. He says there has been nothing from the Inquiry about this man.

Temple said that, in comparison, ‘Jackson’ was a much more talkative figure, whereas Sloan was very quiet, and ‘made no impact on me’. He does not think that Sloan held any positions of responsibility in the group.

EMERGENCY CONFERENCE

The next report [MPS- 0739470] is on an emergency conference that was held during the weekend of 26-27 June 1971. Some members had been expelled from the Communist Workers League (described as the ‘inner caucus of the INLSF’) a few weeks earlier. You couldn’t possibly resign from the group, you were expelled, and more people left at this ’emergency meeting’.

Temple remembers being warned (by Davoren and Joe O’Neill) that ‘Alex Sloan’ was working for the police. However, at a meeting where this was going to be discussed, despite personally believing that Sloan was an undercover, Davoren accused O’Neill of slander for suggesting that Sloan was a ‘pig’.

Being accused made Sloan’s position in the group untenable, so he left. According to Temple, he did so on amicable terms, with no animosity.

Temple doesn’t know where the idea of Sloan being a police spy came from or what evidence there was for this; and after he disappeared, no further research was done either.

He clarified that he continued working alongside Davoren between June and September 1971, but after this he had very little to do with the guy and his new group.

Temple says he was no longer actively or officially involved in much political activity after this; he would occasionally attend events but not organise so much.

Altogether, there was not a lot we learned form Dr Norman Temple. Most of what he said was common knowledge, at least for anyone who had look at some SDS reports on that period.

Witness statement of Dr Norman Temple

INFORMATION ACCESS

Those following proceedings from home, including journalists, found themselves hampered by the continual references to documents that still hadn’t actually been uploaded to the Inquiry website. Some of the exhibits were uploaded earlier on in the day, but not all of them.

The way they were presented on the Inquiry’s pages of the hearing makes it near-impossible to look at them as they’re being discussed. With multiple reports entitled – for example – ‘Special Branch report by HN347 on a private meeting of the INLSF’ there is no way to work out which one is being referred to.

We do need the unique reference number included there, and of course the complete selection of files referred to at the start of the hearing – adding them later on is all too confusing.

ROOFING ROUND-UPS

For those of you who need an even shorter summary of the day and some added comment of your independent experts, have a look at Tom B. Fowler’s roofing round ups, the venerable spycops hearings live tweeter bringing you instant reaction to the hearings given live through the day during the breaks on Facebook.

Yesterday the police told the Inquiry said they would have behaved identically if a racist campaign had opposed a black sports team touring England. But supporting racism is different from opposing it. Equivocation between the motivations and actions of the left and far-right was apparent in the witness testimony of Madeleine earlier.

Yesterday the police told the Inquiry said they would have behaved identically if a racist campaign had opposed a black sports team touring England. But supporting racism is different from opposing it. Equivocation between the motivations and actions of the left and far-right was apparent in the witness testimony of Madeleine earlier.