UCPI Daily Report, 11 May 2021, part one

Tranche 1, Phase 2, Day 14, part one

11 May 2021

Evidence from witness:

‘Vince Miller’ (HN354, 1976-79)

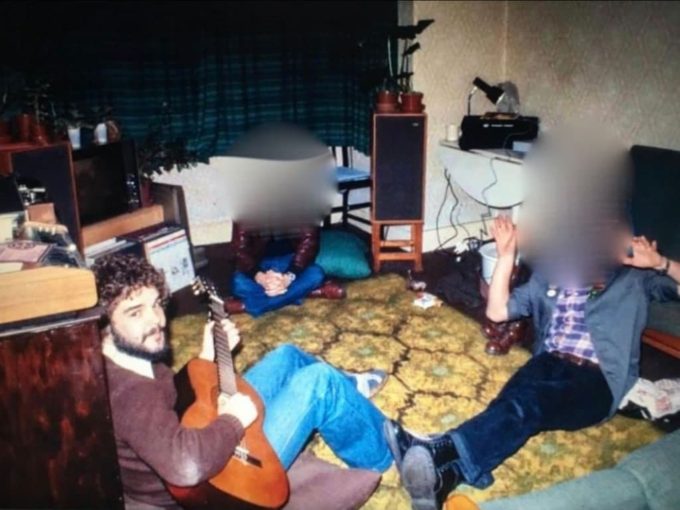

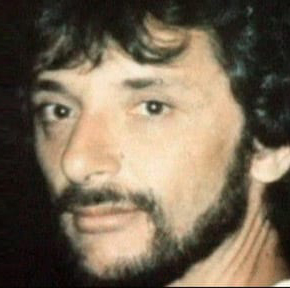

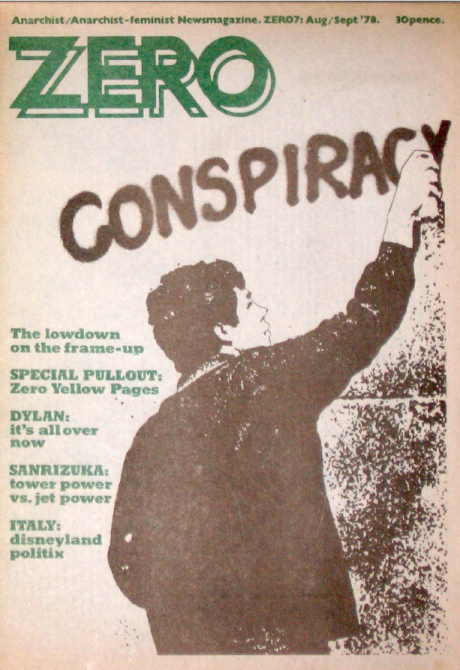

Special Demonstration Squad officer ‘Vince Miller’ while undercover in the late 1970s

The 11 May hearing of the Undercover Policing Inquiry focused on a single police witness: Officer HN354 who, as ‘Vince Miller‘, infiltrated the Socialist Workers Party (SWP) from 1976-1979.

Miller has submitted two written statements, one written on 18 November 2018 and a second (supplementary and consolidated) statement written on 10 March 2021.

During his deployment, he had sexual relations with four women that we know of, including ‘Madeleine’ (a member of the Walthamstow branch of the SWP) whose compelling evidence we heard yesterday. Madeleine’s written statement is also available.

Miller disputes some of Madeleine’s account of their relationship.

Miller was questioned by David Barr QC, Counsel to the Inquiry, whose performance was notably focused and sustained, keeping the pressure on highly significant issues. Though we have been critical in the past, it is just as important to note when he shows himself the right person for the job.

The day was particularly long by Inquiry standards and covered a vast amount of ground; so much so that this report will focus on the earlier part about his joining the Special Demonstration Squad and abuse of women. We will publish part two, covering the political activity he was involved in and end of his deployment, separately.

TESTIMONY BEGINS

Asked whether he was interviewed before joining the Metropolitan Police’s Special Demonstration Squad (SDS), Miller it was nothing more formal than a casual discussion about what would be involved.

He remembered that one of the first things they asked about was his marital status. Miller explained he was the first unmarried undercover to be deployed. He was in a relationship at the time, but not cohabiting. He thought being married was preferred, because having a wife meant some form of support whilst enduring the stress of an undercover deployment.

BACK OFFICE & REPORT WRITING

There were only a certain number of officers in the field at a time, so he worked in the unit’s back office until there was a ‘vacancy’.

He would take calls from undercovers and pass on messages. He said that reading undercovers’ reports provided him with ‘snapshots’ of information, and the content and style expected in the SDS.

Miller provided some new insights into the reporting process. As SDS reports were based on intelligence from undercover, they were given a higher security classification than standard Special Branch ones. He said the Registry File references which appear in the reports attached to names and groups were added by back office staff like himself. Sometimes information from various officers would be merged into one report, or split; this was done by management, who would also check the reports.

A document [UCPI0000010718] from July 1976 refers to a photograph of a Revolutionary Communist Group member being shown to informants at the request of the Security Service (MI5), and the individual being ‘positively identified’ as a result.

Miller added:

‘I would say that almost every report that was submitted on the groups we were working with would be copied across to the Security Service.’

He says that Superintendent Derek Kneale would visit the SDS back office every hour, and sometimes visit to the safe house. Kneale knew the squad ‘very well’.

LEARNING THE TRADECRAFT

Asked how he learned his tradecraft, Miller said the spycops shared tips amongst themselves, such as what vehicle to get. He came to know all his contemporaries during his time in the squad.

Together, they attended meetings at the safe houses twice a week. Occasionally, officers would talk to the managers in private – ‘managers always made themselves available’.

However, they also gave the deployed officers leeway, as there was no communication once in the field.

SWEATING

The next question was a crucial one: whether he received any guidance on personal relationships with activists. Miller says he cannot remember any discussion about this.

Barr then read from the ‘gisted’ (summarised and censored) statement that Miller had previously submitted to the Inquiry [UCPI0000034356], which noted an individual was keen to start a relationship with him.

It said:

‘[Miller] did not reciprocate for the very reason that this was contrary to SDS directions, morally questionable and could have compromised his deployment.’

Contradicting what he had said earlier, this was just the first of various inconsistencies in Miller’s testimony. It was from this point that his demeanour changed from the relatively relaxed to more nervous. Eventually, he could be seen sweating.

Miller said this woman’s approach to him was half way into his deployment and confirmed she was not one of the four he admits having sex with. He says he had no physical sexual relationship with this woman, but she ‘very much gave the impression’ of wanting one.

He also confirmed a private conversation between him and the SDS head, CI Geoff Craft (HN34), about it:

‘I said I thought it was becoming an issue, and… asked what his opinion would be if such situations developed. He then said that he didn’t think it was a very good idea.’

He clarified that this advice referred to both a relationship and sex. He also admitted it was good advice, which he should have followed.

Barr probed what Miller had meant by ‘morally questionable’:

‘Because we were not being totally honest with the other persons involved in the relationship.’

Barr steadily drew Miller out through his questioning, and got him to admit:

‘If it’s sexual extending over a long period of time, I’d have definitely said that was wrong, yes.’

And whether a one-night stand in his cover name was also morally questionable?

‘I now have to accept that was an incorrect act.’

COMMITTING CRIME

Miller was asked about guidance on undercover officers committing crime. He said that they were told to avoid carrying heavy wooden banner poles at demos in case ‘an enthusiastic police officer’ thought they constituted offensive weapons.

He also admitted to drink-driving during his deployment, explaining it was:

‘considerably more common then than now.’

On ‘legal professional privilege’ – confidnetiality between lawyer and client, which was breached by officers who were arrested when undercover – Miller said he was aware of the concept but not the term.

SUBVERSION – IT’S WHAT MI5 SAYS IT IS!

Ask about his understanding of ‘subversion’, Miller said that ‘to be brutally honest’, he was not ‘really concerned’ about the definition of it – it was whatever the Security Service defined it to be. If they said an organisation was subversive, it was good enough for him.

Pressed further he said:

‘I think the subversive would seek to change things without going through the parliamentary system.’

Although asked if there was any guidance on what he should and shouldn’t report, he instead gave an answer on who was and wasn’t to be reported on. He said that MPs shouldn’t be and ‘you had to be very careful with reporting journalists’.

Miller made the point he ‘was essentially a foot soldier’, and if some information seemed sensitive would seek authority or permission from his managers.

IDENTITY THEFT

He was also asked more about how he created his false identity, ‘Vince Miller’. It was standard practice for SDS officers to steal the identity of a dead child as the basis for their undercover persona. He thought it unlikely that the deceased children’s family would find out, so did not worry about this. Nor had he given consideration as to how they might feel if the identity theft ever came to light.

Asked how he felt, upon reflection, so many years later, his response was neither to apologise or express regret. Instead he spoke of how current technology has made the practice obsolete.

This is another theme of Miller’s evidence; despite clearly being distressed by some of his actions, or at least being made to acknowledge their consequences, he never steps up to take this opportunity to make amends, nor offer any apparently genuine contrition.

Miller did several things to make it harder for anyone to delve into his identity, for instance choosing a child with no father listed. He also picked a different first name to use, ‘Vincent’ being neither his or the dead child’s real first name.

He had a fake job with a firm installing Portakabins, partitions and suspended ceilings. This was a real firm, and he set things up with them so if anyone called for him, they would say was out and about, the job supposedly taking him to different work sites. This was, he said:

‘a good buffer to keep the communications under some kind of control’.

FEAR OF BEING FOUND OUT

Though there was ‘constant concern’ about being identified as a police officer, Miller had no contingency plan. Officers were told to contact the SDS office immediately if anything happened.

Miller relates how he was once recognised by a uniformed officer at a demonstration. To his good fortune, the officer didn’t approach him at the time, but he did report Miller’s involvement in this activist group to New Scotland Yard.

He seems to have made up some elements of his ‘legend’ on the spur of the moment to deal with questions as they arose. Some stand out as they have been used by various other spycops. In response to a question about what he was doing at Christmas, he said his parents had died, effectively ending that line of conversation.

He made up a story about a previous ‘toxic’ relationship to explain his lack of a record collection and other belongings. He says it was ‘purely and simply to explain the circumstances under which I was living’, adding that his bedsit was the sort of place that nobody would want to stay for long.

Despite these similarities to the cover stories of colleagues, Miller says he has no idea what other spycops officers’ legends were. Rather, he was able to draw on his personal experience of a break-up to inspire his cover story.

WALTHAMSTOW SWP

He was told to find a group in Walthamstow to spy on. He chose the local branch of the Socialist Workers Party (SWP).

Asked why they were a suitable target, he said the SWP were:

‘defined as subversive by those who are more expert in that field’

He added that the Waltham Forest branch ‘was an active group’.

Miller says the Walthamstow SWP was the only group he joined. In another of his inconsistencies, he then played the need to target the Socialist Workers, saying the SDS regarded the party as a ‘feeder organisation’ from which they could move to other groups:

‘One from which you could be disaffected and join a less populist, more idealistic line.’

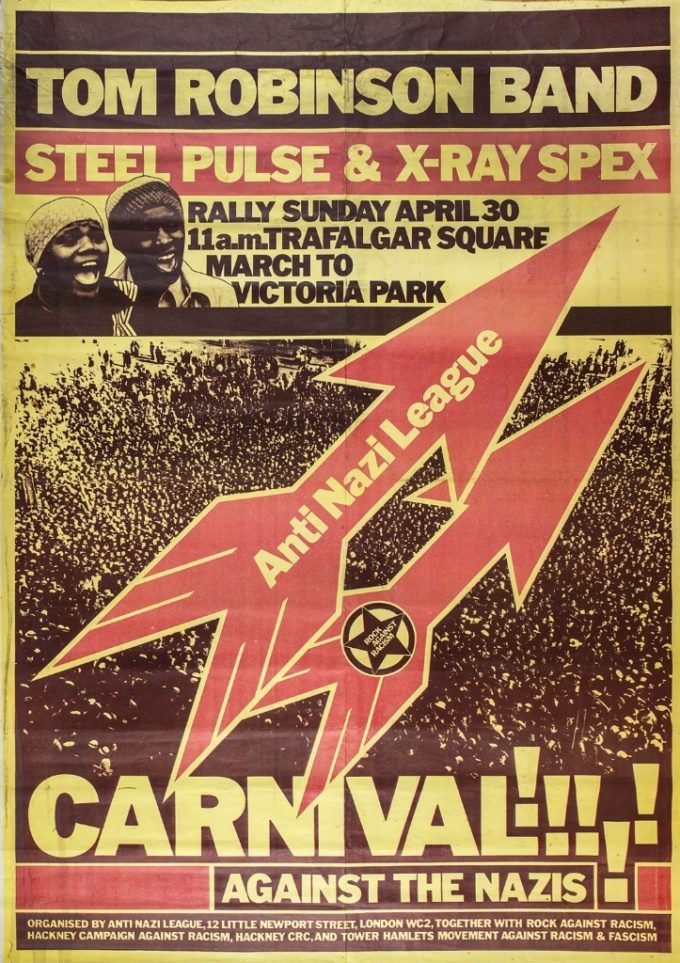

Rock Against Racism carnival poster, 30 April 1978

Later he said he used his position in the SWP to meet more people, to cast his net wider, though little evidence of that has been provided in terms of his reporting.

It was easy to infiltrate the group – he just approached local paper sellers and they invited him to their public meetings at the local pub, the Rose and Crown.

Asked whether he influenced the direction of the group, Miller says he deliberately chose not to read up on left-wing theory before joining the party. Instead he presented as ‘politically naïve’, waiting for the party to educate him about politics.

Once Miller joined, he attended pickets and other demos, as well as birthday parties, socials and fundraisers. He was even on the social committee of the Outer East London District.

However, he only remembers attending one music event – the Anti Nazi League’s large Rock Against Racism concert in Hackney on 30 April 1978.

He would also help members of the group move house, and go to the pub with them during and after meetings and other events. He would go back to their houses, where drinking would continue.

OFFICIAL: NAZIS ARE NOT SUBVERSIVE

Barr asked Miller if he considered infiltrating the far right, to which Miller gave the curious reply:

‘I don’t think I should talk about the far-right deployments at this stage.’

Throughout the hearings, it is clear that the SDS had a political bias against the left and were seemingly wilfully ignorant (at best) of the dangers the far-right posed.

Miller followed this line no uncertain terms:

‘I’m not sure at that time [the far right] was classified as subversive, and therefore would not have been within our remit.’

He did not mention the public order part of their remit, or the general policing requirement to stop murders, violent assaults, arson, harassment and property damage being perpetrated against Black and minority communities.

BOOZY AFTERNOONS AT SDS SAFE HOUSES

The meetings at the SDS safe houses were attended by the undercovers, the managers, office staff, any new recruits, and occasionally more senior officers. The safe house he recalled was a large flat, with two or three bedrooms, and a living room where the group met.

Miller would submit his diaries and written reports – usually hand-written, although he thinks typewriters were issued later. They would sometimes get feedback if these reports were not at the desired standard. He had several corrections on compliance with Special Branch’s house style.

Asked about the topic of conversations at the safe house, he said they would discuss likely attendance numbers at demonstrations. They would work together to identify individuals (e.g., from an album of photos which was passed around).

Miller went on to explain the value of the peer support – there was nobody else these officers could discuss issues with, as they could not talk to their families about their work:

‘And of course, because this was a rolling group, there was almost every likelihood that what you were finding difficult as a new field officer had been met by somebody else, who had said, “look, I tried this and it did work,” or, “it didn’t work”. It was very much a laid-back thing as the afternoon went on. Which is where you’d got a sort of informal exchange of information, but also a release so that you could actually talk about things somewhere.’

He said these afternoons were ‘relaxed’ and ‘laid back’, and suggested that they got more so, especially if the spycops were drinking. The managers would leave at some point and the undercovers stayed until it was time to go to their political meetings in the evening.

‘We were doing a job that not many people could or would do, and it was valuable’

He says that there were always opportunities for SDS officers to discuss welfare issues with their managers, but:

‘we’d probably have turned it down even if we needed their help.’

Such discussions also included the demands of being deployed in the different groups. For instance, those spying on the Maoists complained about how much reading they had to do.

However, Miller noted they couldn’t just ‘sit on the outside and take the Mickey’ out of their targets – they had to take them seriously and have some respect for their political beliefs in order to be effective.

‘I think police officers have to deal with what they have to deal with, and you just have to accept that people have strange views and our views that don’t chime with yours, and cope with that.’

NO BANTER

Asked about the kind of ‘jokes’ that were told, Miller spoke of the need for ‘stress relief’. However, he claimed they were more likely to joke about other police officers than about their targets.

Unlike the account in the witness statement of his colleague, ‘Graham Coates’ (HN304, 1975-79), he does not recall any banter about individual undercovers or any ‘sexual jokes’:

‘It was not like the stereotypical rugby club atmosphere after the match type atmosphere.’

In particular, he denied hearing any banter like, ‘he’ll have made her bite the blankets again last night’ (a cringingly unforgettable piece of evidence from Coates’ evidence a few days previously).

Asked if any of the jokes might have been considered offensive by feminists at the time he said:

‘Someone may well say “did you hear the Jim Davidson joke of last night?” His humour would no longer be acceptable, but that might be going round and you’d be told that.’

Later he insisted he didn’t remember any racist joking or opinions, ever, by anyone, and says he is ‘absolutely certain’ of this. He added that he was only referring to the SDS, not the entire police service, when he said this.

Did the managers join in with banter? His response to this question was about people ‘having different personalities and ways of interacting’.

REPUTATIONS OF OTHER SPYCOPS

Next, Barr turned to asking questions about other SDS officers’ reputations with women.

He began with Richard Clark (‘Rick Gibson’ HN297, 1974-76), who had sexual relationships with four women including an activist called Mary. Miller confirmed Gibson’s reputation as a ‘ladies man’, but says he only knew of this after the officer had moved on from the SDS. They remained friends after their deployments.

What about ‘Jim Pickford‘ (HN300, 1974-76)?

‘He probably crossed the line.’

Miller said that Pickford never spoke to him about sexual relationships, or about falling in love (not just with activists but with anyone):

‘I think I heard stories when he was getting married for the second or third time.’

Next, he was asked about ‘Barry Tompkins’ (HN106, 1979-83). He said that that officer was ‘somebody who enjoyed the company of women’, but that he didn’t try to seduce any in Miller’s presence.

Miller says his deployment didn’t overlap with that of ‘Phil Cooper’ (HN155, 1979-83) but recalled that he ‘got into all sorts of scrapes’ – mentioning ‘women, drinks and all sorts of things’. He doesn’t remember any rumours about Cooper having sex while undercover, but:

‘I wouldn’t put it past him.’

BANTER?

Barr tested the consistency of the day’s witness evidence, by returning to ask again about the jokes and banter – did he hear any on the subject of the spycops having sexual relationships?

Miller insisted that it:

‘was never a subject of banter in my presence.’

Barr then followed up on evidence from previous days about manager turning a blind eye. Miller said he isn’t sure if they were even aware of the relationships:

‘It was certainly never openly said, “yeah, get on with it” or anything like that.’

Last week we heard ‘Graham Coates’ describe how he was granted permission to transfer his attention from the SWP to anarchists, at his own request (because he says he personally found anarchism more ‘fascinating’).

How important was officer retention to the unit’s managers? Did this mean that undercovers’ requests were accommodated wherever possible?

‘They were generally tolerant of our requests. I don’t know if there’s a particular line here, but yes, they were very supportive and understood that you would make requests at certain times.’

HEAVY DRINKER

Asked about his alcohol consumption, Miller said he would drink every day and would have, on average, three pints, while the other SWP members sipped on a half a pint.

In her evidence, Madeleine said he was ‘always first to the bar’. Miller quickly agreed with this, seemingly proud of his reputation as a heavy drinker. Pausing for thought, he then said this was part of his tradecraft.

In particular, he claimed, he got into the habit of going into the pub ahead of the others in order to check who else was there, and ensure there was nobody who would recognise him in his real identity. He says even nowadays he still does this, and tends to position himself with his back to the wall in pubs.

BACK TO WALTHAMSTOW SWP

Miller says he got to know Wlathamstow SWP branch members well, however, wasn’t ‘an expert on their private lives’. He didn’t spend as much time with the married members of the branch, who had their own personal and professional lives going on.

However, he kept a distance between himself and the activists generally, and kept communication under control. He didn’t invite them round to his cover flat, he didn’t make himself easily available. He chose when to spend time with them.

Barr asked about him spending time at SWP members’ homes. He recalled the house-share where ‘Madeleine’ and other members lived. What did he know about her?

‘I believe I knew that she had been married and was no longer with her husband, and pretty much that was it.’

He was reminded that he filed a report in July 1978 [UCPI0000011289] about Madeleine’s wedding, which had taken place in 1976. Was this usual practice?

His excuse is that there was already a Special Branch file open on Madeleine, and he was simply making sure it was kept up to date. He says he didn’t attend the wedding, and doesn’t remember meeting Madeleine’s husband (also a SWP member).

However Madeleine’s evidence contradicts this – she says he visited the couple’s flat.

WHITE SHIRT

There followed an unusual line of questioning – about whether he wore a white shirt during his deployment. In his statement, Miller denied doing so. However Madeleine has provided the Inquiry with photographs taken of him back in those days, and he can clearly be seen in what looks like a white shirt.

Miller quibbled about the photograph – how could they tell what colour the shirt was, given it was a black and white image? When pressed, he did concede he wore white shirts on occasion, but couldn’t quite bring himself to admit that his original statement was, as Barr charitably put it, ‘mistaken’.

Though these sort of exchanges appear trivial or odd, there are generally solid legal reasons to this strategy, which was particularly highlighted by the evidence of both Madeleine and Miller. In this there was a dispute of fact around the relationships, so in asking these questions Barr was starting to test the veracity of Miller’s account.

It is a problem that it is not being done properly by the Inquiry in other cases, such as when undercover ‘Dave Robertson‘ (HN45, 1970-73) disputed Diane Langford’s account of his exposure. However, it is heartening to see the Inquiry do it properly in this particular instance.

RELATIONSHIP WITH MADELEINE

After the lunch break, David Barr QC zoomed in on Miller’s relationship with Madeleine, in what became the most intense set of questioning at the Inquiry to date.

Unlike other sessions, Barr did not let incomplete answers simply stand and move on. If he wasn’t satisfied with the answer he would rephrase the question, and then once again if he thought it necessary.

Barr also compared what Miller said now, to what he had said in his first witness statement three years ago, and in his supplementary statement of this year, and inquired what had caused him to change his mind or brought back memories. Barr additionally picked up on when Miller said something different to what he had stated earlier.

What did not come over in the transcript was Barr’s use of pauses. Miller would often take time before answering, and Barr would let the response linger a bit before moving to the next question. This added to the tension, you could hear the proverbial pin drop in the hearing room as people collectively waited for the next move. Sometimes the questions were just devastating.

Miller squirmed, his quite red face flushing as his body language gave him away. He seemed to want to disappear under the table, looking down, becoming smaller. Only when the topic of Madeleine was finished did he straighten up again.

It’s difficult to capture that tension in this report without having to include too many extensive quotes.

THE RELATIONSHIP BEGINS

Barr started a question to introduce the topic of Miller’s relationship with Madeleine, asking him what Madeleine’s attitude to the police was.

Miller claimed not to remember, but said SWP members generally distrusted the police, as they were more likely to be right-wing. They believed the State would not hesitate to tap their telephones or intercept their mail. The police would often protect the fascists’ demonstrations, and were seen as the ‘repressive arm of the State’.

Miller said his relationship with Madeleine was ‘quite marginal’ before it became sexual in late summer of 1979. They would have met at the weekly meetings, and socially, but always as part of a larger group of people.

He says he has no memory at all of the location when they first got together. Madeleine told us it was a house party in Ilford, and he has no reason to doubt her memory on that.

Indeed, whilst he was wary of admitting much, Miller did not dispute much of Madeleine’s detailed recollection of the start of their relationship; that he was in a chair and she sat on his lap, that they spent the evening chatting and flirting, that neither of them had an excessive amount to drink, and that he drove them back to Madeleine’s flat. What he did question was whether he actually pulled her on his lap.

In his first witness statement he had sought to excuse the four sexual encounters with his consumption of alcohol. Now Miller was clear that he was not blaming it on alcohol, nor on Madeleine:

‘Whoever made the invitation, I could have declined. It is therefore my responsibility.’

Miller said that back at her place, they sat in the lounge chatting with her house mates, when she invited him up to her room. He claimed he was surprised that she would say this with others present.

Barr noted that, as a serving police officer on duty, this would have been the time to say no. He asked Miller for his reasons to decide otherwise. The answer was sobering:

‘I think the prospect of not driving home and spending a pleasant evening continued and overcame my hesitation.’

Barr bluntly asked him; did you go into the bedroom because you wanted sex – despite the fact you were a serving police officer on duty?

‘I think I’d have to say yes.’

ON TAKING PRECAUTIONS

Miller gave no consideration to what would have happened if Madeleine had got pregnant.

In fact he said that, as she was a feminist, it was her responsibility:

Q. Did you use contraception?

A. Not that I recall.

Q. Did you give any thought to the consequences of fathering a child when you were in fact an undercover police officer?

A. No, I didn’t. I think my perception was that as a full feminist socialist supporter, then if there was any need for protection, then she would have mentioned it. I didn’t see her as some kind of shrinking violet, or something like that. This was a member of the women’s movement, and women had the same right to ask for things and to insist on things as a man. And I would have supported that then. I incidentally still do. So she would have had the right – absolute right to insist, if it was necessary.

Q. But in the absence of any insistence?

A. Then I assumed everything was safe. In contraceptive terms.

Despite knowing she was recently out of an abusive relationship, Miller presumes she would never have felt pressured by him.

He remembers using the bad-breakup story as part of his ‘legend’, but while Madeleine recalls talking about it in bed, Miller has no recollection of sharing more with her about this previous ‘toxic’ relationship. Nor does he remember telling her, or anyone else, that he had been grown up in a children’s home.

Miller is not denying her account of this, he just can’t remember it. This was one of the occasions where Miller seemed really close to admitting more. We can only assume that listening to Madeleine’s account the day before had caused him to shift on what he had been prepared to acknowledge in his own evidence.

‘MORALLY QUESTIONABLE’

Barr returned to the passage from Miller’s gisted witness statement and honed in on the phase ‘morally questionable’.

He asked Miller if he thought it was morally questionable to have a sexual relationship over a period of time. Miller responded:

‘I’d have definitely said that was wrong, yes’.

And what about a one-night stand, was that morally questionable?

‘On reflection, I would say it was.’

And at the time?

‘Well, obviously there was an occasion when my worries about such things were overcome. I have to accept that [it] was an incorrect act.’

Miller said it hadn’t occurred to him that his cover story of past pain and not wanting to be hurt again might evoke feelings of sympathy, intimacy and protectiveness amongst those he told it to.

BETRAYAL

Asked if he thought Madeleine would have had sex with him if she knew who he really was, Miller wavered:

‘Difficult to say. If she knew who I really was then possibly she would have liked me, if she knew that I was a police officer then almost certainly not… But I’m both a police office and a person, so she might have seen the person not the police officer. And therefore I can’t really answer that.’

Despite admitting it was wrong that he had manipulated trust built up over several years of knowing Madeleine, Miller objected to it being described as a betrayal:

‘That’s a very strong word… “betrayal” seems to me a little over the top’

It was in this context that Miller said:

‘I think I would reflect on the fact that my field name was out in the public domain for some time and didn’t generate any reaction. So, I think my feeling was that she wasn’t overly concerned by the situation.’

VINCE THE VAMPIRE

Miller claims that his social contact with Madeleine didn’t increase at all after this – he doesn’t remember sitting at tables with her, or having sex with her at least once a week subsequently, as she remembers.

Instead, he pointed out that they were now in different branches of the SWP so didn’t necessarily meet up regularly.

He says they weren’t a couple:

‘we just bumped into each other, as you would, without arrangement.’

Barr kept pressing, saying ‘but you did sleep with her more than once, didn’t you?’

Miller responded:

‘I slept with her on the first occasion is the only one I remember.’

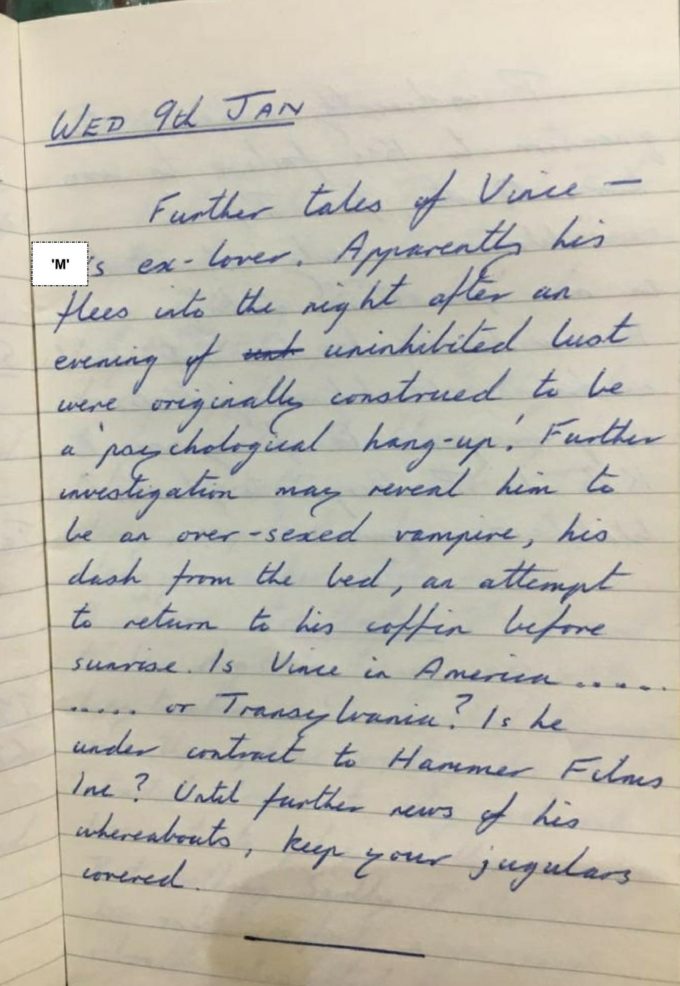

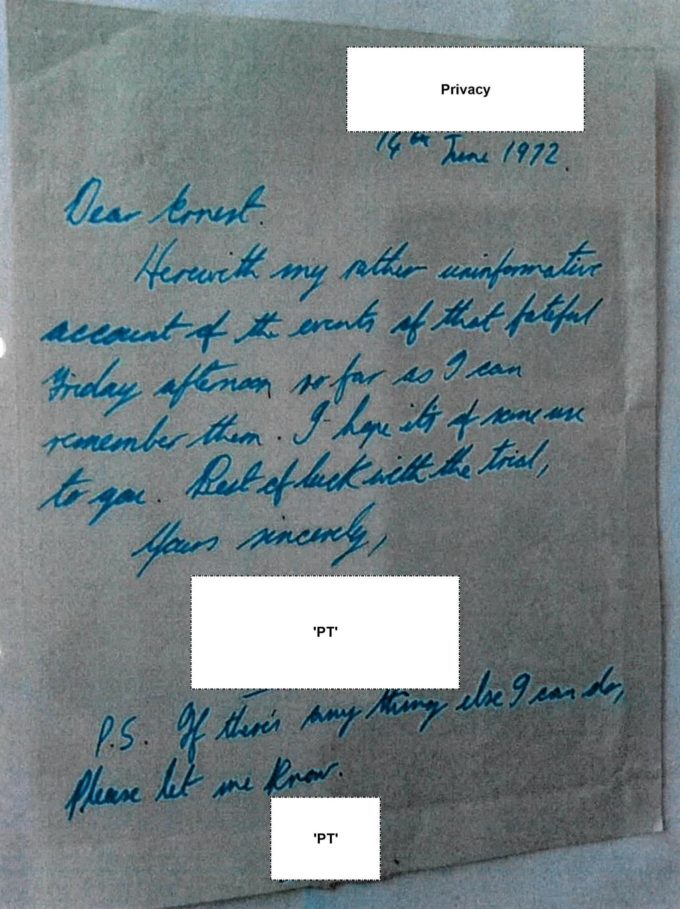

Madeleine’s relationship with Miller described in a friend’s diary, January 1980

The Inquiry showed an extract of a diary entry from 9 January 1980 [UCPI0000034310], written by a friend of Madeleine’s, describing Miller’s habit of leaving her bed in the dead of night and never staying over until morning. It memorably described him as an ‘over-sexed vampire’.

As Miller agrees he stayed over the first night, this must refer to a number of subsequent occasions, Barr noted.

Miller avoided the point by saying arguing it was not a contemporary document as Barr claimed.

Barr replied unwaveringly: ‘I said near-contemporary..

Miller apologised for being aggressive and, with that, managed to avoid answering the question, though he did not challenge the accuracy of the document.

A RELATIONSHIP

Ask more about Madeleine’s memories of the time, Miller said he didn’t think it was necessarily obvious that she was fond of him, and wanted more of a relationship with him.

He says they remained on friendly terms. He repeatedly stated that he had little or no memory of many events in this time. Particularly, while Madeleine has clear recollections of the last time she saw him – at his leaving do, when he was with another woman – Miller said he has no memory of saying goodbye to her before he ended his deployment.

Asked if having a sexual relationship with Madeleine would enhance his cover, Miller gave an excuse heard from other spycops:

‘If you’ve been out in the field for some time and not had any relationships, people are inclined to wonder why.’

This is flimsy at best. Many people go for long periods without being romantically involved with others. Indeed, the reason officers like Miller tell stories of historic heartbreak is precisely because it is a credible reason to be emotionally distant.

Given a final opportunity by Barr, asked if he had anything to add about Madeleine that had not been covered yet, Miller squirmed:

‘I think with the benefit of more maturity and hindsight, and less stress, then I will say that the night we spent together was inappropriate and unprofessional. There was no intention – sorry, can I say that again?

She was not targeted in any way; it was not any part of any kind of system; it was not something either expected by the management, or indeed expected by my peer group, to show you are one of the boys. It was in fact something that happened at a convivial evening.

And that’s how it happened, how I reviewed it… I never discussed it with anybody, until these events [the Inquiry], where I felt that total openness and honesty would be what was required.’

This is when the Chair, Sir John Mitting, came in with a question of his own.

Mitting stressed that Madeleine had impressed him when giving evidence:

‘As a sincere and essentially truthful person, trying to tell me, as best as she could remember, what happened between you and her.’

Mitting said he could accept people remembering things differently, but could Miller explain:

‘Is it a case, as can happen in life, of two people remembering a series of events differently? Or is it something more than that?

‘My understanding is that you do not say that she is consciously or unconsciously making this up, you accept that her evidence is genuine; your recollection remains different. I’m simply seeking to ask if there is any reason why your accounts are, in significant respects, different. If you could help me, I’d be grateful.’

Miller responded in couched terms, effectively saying that she could be making it up to make spycops look bad, even though he knows it’s not credible to suggest:

‘It would be inappropriate, I think, for me to suggest there was any other motive for her in trying to diminish the reputation of undercover officers, but that thought would cross my mind… I’m sure you’ll correct me, that if there was any other explanation, that’s the only one I could furnish.’

THE SECOND SWP WOMAN

Barr next asked Miller about another SWP member he reported having sex with. The former undercover described her as being less involved in the Party than other members.

He got together with her at the very end of his deployment, after he’d announced his impending move to the USA. They drank together, and he said he spent one night with her, then met her at a few other party events including his leaving meal.

He agreed that she was unlikely to have had sex with him if she’d known he was an undercover police officer.

Again, he didn’t give any thought to that at the time:

‘It just seemed a happy way of finishing the evening.’

Again, he did not use contraception or consider the risk of pregnancy.

Miller says he never told anyone at the SDS about these relationships.

THE OTHER TWO WOMEN

Miller was then asked about two other women he deceived into relationships which he also recalls as one-night stands. Both incidents were in the early days of his deployment.

He claims there were no links between these two women and the SWP, he just met them in the pub when he was getting to know the environment he had to infiltrate.

Since they were not related in any way to his target group, he had not thought it necessary to mention them in his ‘impact statement’ to the Inquiry. Nor did he come clean when his solicitor was sent a letter by the Inquiry specifically asking for details of all sexual relationships.

He says the circumstances around both were similar, but cannot he recall much else other than that neither woman wanted to continue the relationship.

A point not particularly drawn out was that this was while he was undercover and claiming expenses.

Barr then moved to the issue of how this could have been prevented. If Miller had had stricter guidance from the SDS, does he think he would’ve avoided having these sexual encounters, or it would have just ensured he kept quiet about them?

Miller said he would have made ‘different decisions’ if there had been a ‘stricter regime’:

‘We were completely alone out there, making our own decisions; there was no way of getting support or guidance like that… For me, I guess I’d have needed firmer and more rigorous questions about my activities.

Barr picked up on Miller’s earlier statement of official guidance ‘falling on deaf ears’ so, if there had been any extra guidance, would it have been treated seriously by him or fellow spycops?

Miller changed tactics:

‘it may well be a case of the personality saying it – more than the actual message, that may have had the effect.’

He was asked if there were any qualities which would make someone unsuitable for this kind of undercover work?

Besides the need of a ‘strong personality’, Miller jumped back to saying, ‘I would not consider myself an active womaniser’, before adding that there were some people who would be indeed unsuitable for spycops work.

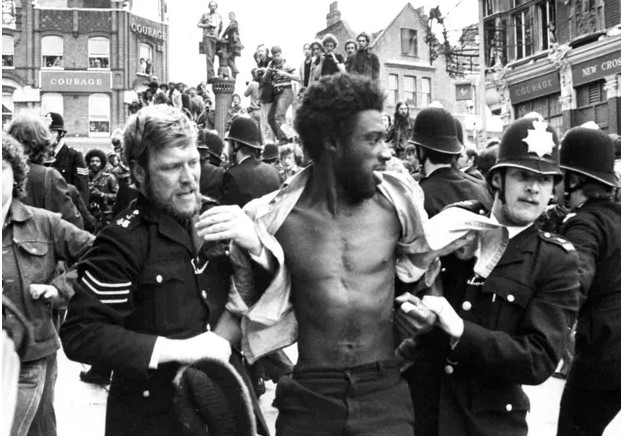

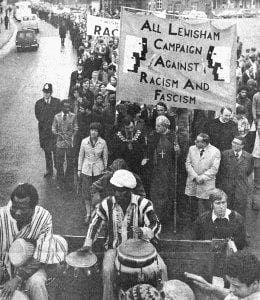

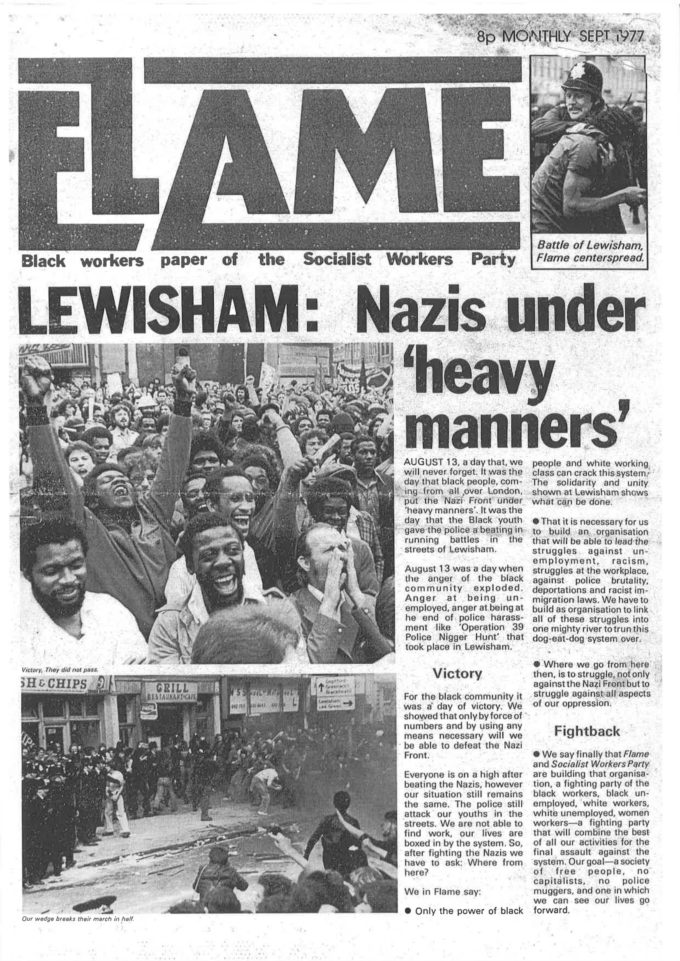

With that, the questioning on Madeleine and Miller’s other relationships came to an end. For the last quarter of the day, the Inquiry moved on to protests and other activities, including his role as a SWP steward at the August 1977 confrontation between fascists and anti-fascists at the ‘Battle of Lewisham’.

We will cover Miller’s illuminating testimony on those things in a separate report.

Written supplemented witness statement of Vince Miller

More details can be found in last week’s reports, and in

More details can be found in last week’s reports, and in  The

The

The speaker said Grunwick showed that at least a thousand comrades would be needed to attack or block the factory gates, and the plan would need to be enacted swiftly and forcefully to avoid it being stopped by police. The SWP have the ability to take such action, he said, but not the capacity to organise it.

The speaker said Grunwick showed that at least a thousand comrades would be needed to attack or block the factory gates, and the plan would need to be enacted swiftly and forcefully to avoid it being stopped by police. The SWP have the ability to take such action, he said, but not the capacity to organise it. The

The

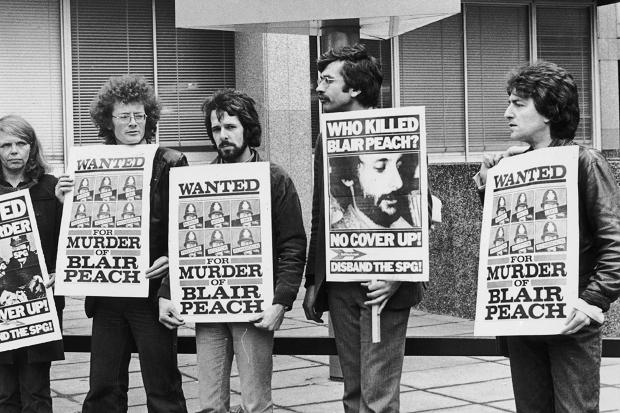

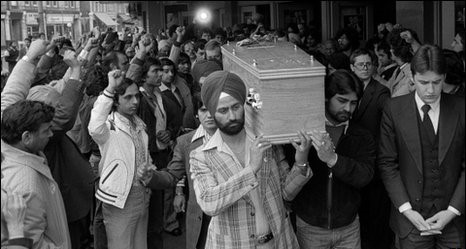

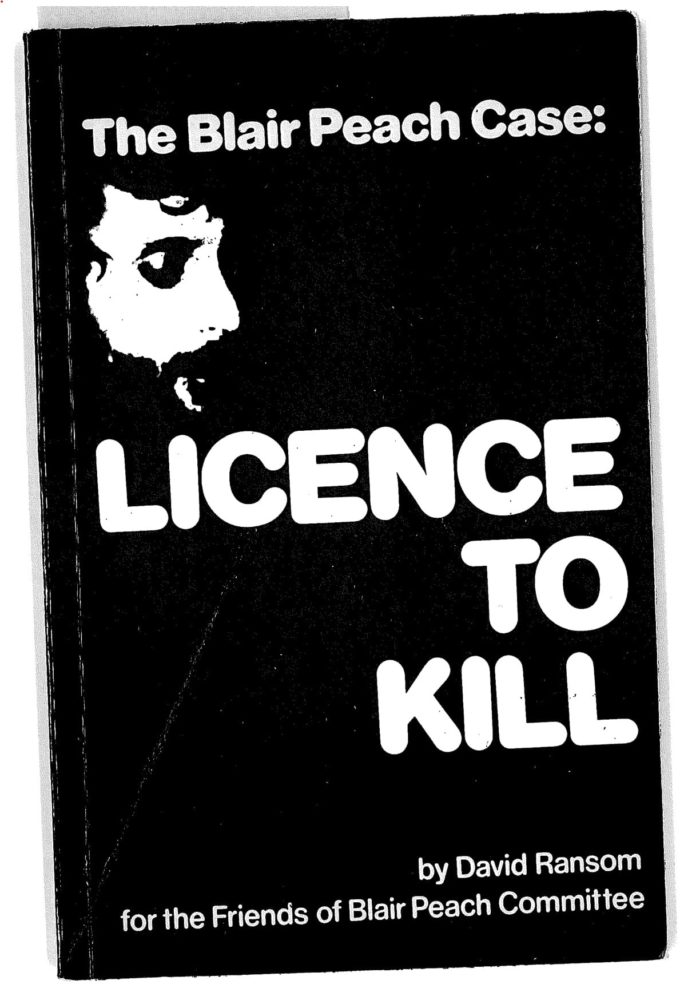

One of Peach’s friends and teaching colleagues, David Ransom, wrote a booklet called License to Kill about the killing of Peach and the Special Patrol Group. The chapter on the Special Patrol Group (SPG) is being published by the Inquiry along with the Cass report [

One of Peach’s friends and teaching colleagues, David Ransom, wrote a booklet called License to Kill about the killing of Peach and the Special Patrol Group. The chapter on the Special Patrol Group (SPG) is being published by the Inquiry along with the Cass report [

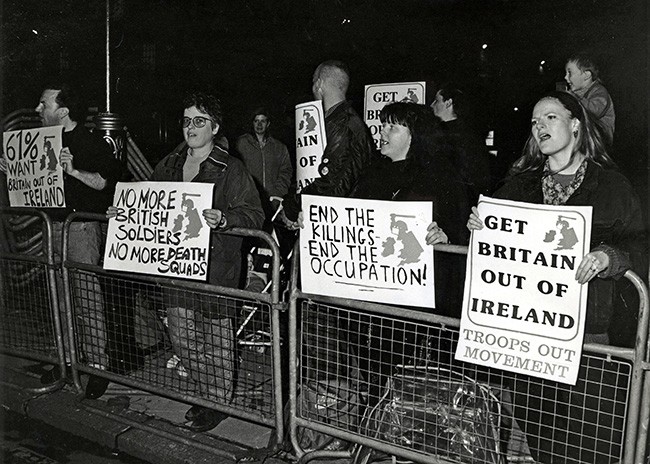

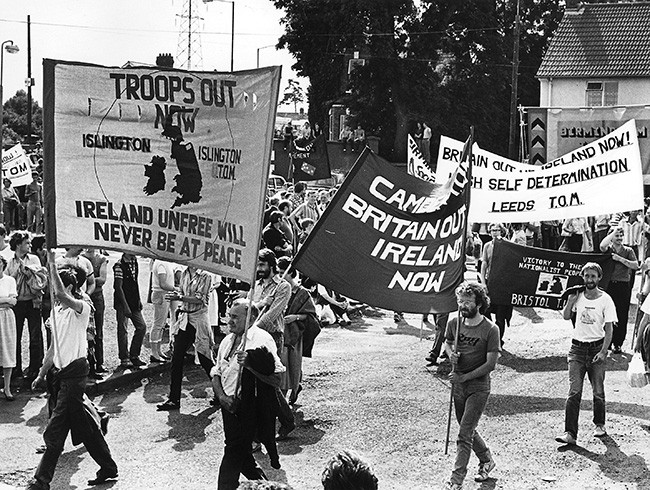

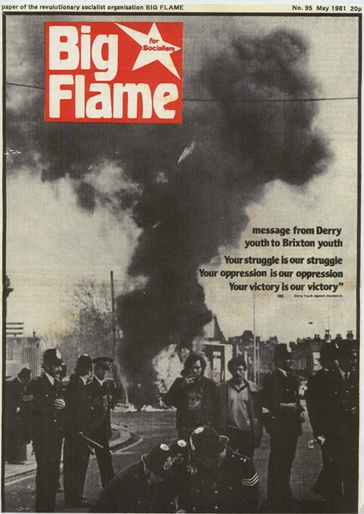

Chessum recalled that to counter the influence of these groups, an informal alliance had formed between Géry Lawless, other ‘independents’ within TOM, and members of Big Flame.

Chessum recalled that to counter the influence of these groups, an informal alliance had formed between Géry Lawless, other ‘independents’ within TOM, and members of Big Flame. Big Flame had been described as ‘libertarian Marxists’ and the Inquiry asked Chessum to explain what that meant. He said they differed from the more authoritarian, dogmatic groups found on the left – they didn’t have a strict ‘party line’ and were more open to discussing different viewpoints.

Big Flame had been described as ‘libertarian Marxists’ and the Inquiry asked Chessum to explain what that meant. He said they differed from the more authoritarian, dogmatic groups found on the left – they didn’t have a strict ‘party line’ and were more open to discussing different viewpoints.

‘

‘

This is the second of our weekly reports on the current round of Undercover Policing Inquiry hearings examining the actions of the Metropolitan Police’s undercover political unit, the Special Demonstration Squad (SDS), from 1973-82.

This is the second of our weekly reports on the current round of Undercover Policing Inquiry hearings examining the actions of the Metropolitan Police’s undercover political unit, the Special Demonstration Squad (SDS), from 1973-82.