UCPI Daily Report, 11 May 2021, part two

Tranche 1, Phase 2, Day 14, part two

11 May 2021

Evidence from witness:

‘Vince Miller’ (HN354, 1976-79)

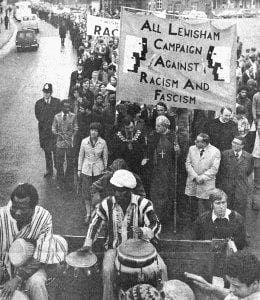

![Anti-racist protesters, Lewisham, 13 August 1977 [Pic: Syd Shelton]](http://campaignopposingpolicesurveillance.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/Anti-racist-protesters-Lewisham-13-August-1977-680x441.jpg)

Anti-racist protesters, Lewisham, 13 August 1977 [Pic: Syd Shelton]

The first post focused on his joining the Metropolitan Police’s Special Demonstration Squad and his deceiving women into relationships.

This one covers the political activity he was involved in during his deployment, which centred on the Wlathamstow branch of the Socialist Workers Party.

THE BATTLE OF LEWISHAM

Battle of Lewisham plaque, erected on the corner of New Cross Road & Clifton Rise in 2017

The anti-fascist protest of 13th August 1977 known as the ‘Battle of Lewisham‘ has come up at the Inquiry several times already, but Miller’s material sheds more light on events.

The fascist National Front (NF) were planning another of their marches through areas with ethnically diverse populations, and a wide range of anti-racist groups were mobilising to stop it. As it turned out, the NF were stopped on the day, and it is now celebrated as a turning point that began their decline.

The Inquiry showed a ‘minute sheet’ [MPS-0733365] circulated two days before the protest.

This was attached to an internal Special Branch report about the tactics the police expected left-wing counter-demonstrators, including the Socialist Workers Party (SWP) that Miller infiltrated, to use in Lewisham.

The document says it:

‘shows that the SWP are determined to provoke a violent confrontation with the National Front.’

Miller agreed with this description of the SWP’s aims.

Inquiry counsel explained they think this report was sent from the Commander of Operations in Special Branch to the head of the Metropolitan Police’s Public Order division (‘A.8’). Miller wasn’t certain whether any of this intelligence came from him:

‘I can’t say definitely, but I would expect it would have contributed.’

Miller says that his SWP comrades had asked him to steward the anti-fascist demo, and so he was up late the night before. He does not remember if the SWP squatted a house in Clifton Rise or not, nor the names of the roads the march was due to move along.

According to the report, the SWP set up ‘protection squads’ (two from each branch) to keep an eye on railway stations and other key locations in the area. These were to be made up of six ‘heavies’, according to the report. Another, ‘specially selected’, squad would be mobile, on the look-out for fascist sympathisers to attack in the streets.

It says that the SWP’s plan was to:

‘attack, harass and intimidate the National Front, with the ultimate aim of creating a riot situation, and attempt to isolate the rear section of the NF column between Clifton Rise and Malpas Road SE4, using buildings and shoppers as protection against police action’.

There was talk of blocking the NF march with a vehicle if it tried going via Amersham Road, and of the anti-fascists regrouping near Lewisham station if the NF got past Malpas Road.

Miller remembers that everyone who opposed the NF agreed that the far-right had to be stopped from marching through New Cross, and that they all organised and planned to stop it. However, he doesn’t remember much of the detail involved in the various tactics listed above, though aspects were not unfamiliar.

Asked if this determination to stop the march was the result of the NF’s ‘swaggering’ (a descriptor that anti-racist campaigner Peter Hain used in his testimony) through the streets and their intimidation of local communities, he said the NF were ‘deliberately confrontational’, adding:

‘I don’t think these situations would be allowed to take place now.’

Miller recalled how the NF was headed by a ‘full colour party’ carrying Union flags and drums. There was ‘taunting and unpleasantness’ between the two groups.

He says he attended the stewards’ meeting the night before. There were probably a handful of others from his SWP branch there, perhaps half a dozen.

The Bishop of Southwark leads the ALCARAF banner, 13 August 1977

After the briefing, Miller went for a wander when he claims he saw ‘certain elements’ (none of whom he recognised) placing caches of bricks and other debris in gardens along the likely route, to be used as ammunition the next day.

Miller says he phoned this information into his police superiors, and would also have told them what he knew about the numbers expected from across London.

Some of the counter-protest was organised by the All Lewisham Campaign Against Racism and Fascism (ALCARAF), a broad coalition of local groups including local politicians, church groups and other organisations. Miller does not think he joined their rally in the morning as he was up very late the night before.

Rather, he believes he joined the main demo later on, in the afternoon. He wasn’t there when the police cleared the main road. Instead, when he arrived the NF demonstrators were trying to emerge from a side road. He described ‘missiles flying’ towards the NF’s flag-wavers, but said the group he was with didn’t throw any missiles.

Despite the Met deploying 4,000 uniformed officers, Miller explained that ‘following the march’ was impossible; ‘it was chaos’. The police had no protective gear in those days. In his words:

‘the mounted branch took a complete hammering’.

There were running confrontations all over the area for the rest of the day. Miller described how, after the march was over, members of the far-right were poised to attack the protestors.

Miller said he was ‘too close for my own comfort’ to the confrontations, and that he avoided getting involved in any ‘direct physical violence’ himself. He got separated from his ‘comrades’ and made ‘my lonely way home’ at the end of the day.

Referring to a post-protest report submitted 13 August 1977 by a Chief Inspector [MPS-0733367], Miller says the events of that day caused a lot of ‘concern and investigation and review’ within the Metropolitan Police.

He said he imagines the intelligence he provided (about the bricks, etc) would have been included, but doesn’t seem to have read this report yet. The Inquiry pointed out that they have not found any reference to it, but this may be because it was written immediately after the clashes.

We learned from a report dated 23 August 1977 [MPS-0733369] that Special Branch held a special debriefing for eighteen of its officers. Miller says he was not one of them. He explained that it’s likely that the SDS’s views would have been represented by one or two officers, ‘at a high level’.

He notes the SDS undercovers were disappointed that their pre-intelligence had been ignored, resulting in severe violence. He believes this was the first time riot shields were used by police in Great Britain. Despite that, in the SDS Annual Report for 1977, the Lewisham event is described as a triumph for the unit.

Further down in the report is a section entitled ‘hooliganism’, saying that while parts of the borough were left unpoliced:

‘a large number of coloured hooligans were enjoying the chance to indulge themselves’

Later on he suggested that the SDS were less likely to use words like ‘coloured’ in their reports by this time, and would use other words, eg ‘locals’. He refused to be drawn on what exactly was said in the safe-house about ‘locals, coming out and joining in the general chaos and mayhem’.

With the typical police dismissal of genuine political motivations on the part of demonstrators, Miller commented about how there are young people ‘who enjoy the violence’ and ‘there is an element of youth that enjoyed getting involved in confrontation’.

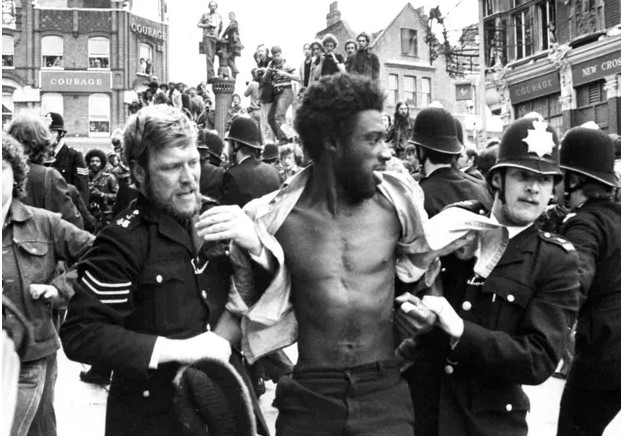

Police detain a man, Lewisham, 13 August1977

He remembers phoning up other spycops after the event, to check they had got home safely. A large number of them were present that day, because they were infiltrating many of the other groups who attended that day, not just the SWP.

They definitely discussed it in the safe-house, he confirmed. He recalled that they were ‘amazed’ that their recommendations – for example, changing the route of the march, to bypass and minimise some of the planned confrontation – were ‘completely ignored’ by the uniformed police.

Once again, it’s notable that police infiltrating the groups at an anti-fascist counter-protest admit they were there in numbers and discussed it. This makes it all the more clear that they are lying when they claim that they were absent from the April 1979 demonstration where police killed Blair Peach, and that none of them remember discussing it afterwards.

According to a report of a meeting at The Crown pub on 17 August 1977 authored by Miller [UCPI0000011196], some members of his SWP group talked about arming themselves with catapults and ball bearings for self-defence. They were preparing ‘for the backlash’ in the aftermath of Lewisham. He does not remember anyone actually doing this, and dismisses it as another example of ‘rhetoric’ that wasn’t necessarily followed up with action.

NATIONAL FRONT ATTACKS

The Inquiry next moved to look at ongoing attacks by the National Front on minority groups and also the SWP. They asked if the Anti-Nazi League’s defence work against racist activity – flyposting, removing racist graffiti, recruiting anti-racists – ever spilled over into vigilantism

‘No, I think that would be a shade too far.’

Miller noted the depth of fear that people had if the NF gained any greater power, and were prepared to oppose them. The Inquiry pressed: do you think your reporting on the SWP protected the public from attacks by the far right?

His answer was that, in the broad sense, his work in the SWP did achieve that – even though he was only doing that work to undermine the group:

‘not, I suppose, if you’re talking about random attacks on individual people… but I suppose, to some degree, my involvement… would have generated more enthusiasm for the general combating the extreme right.’

POSITIONS OF RESPONSIBILITY

Miller was treasurer for the Walthamstow branch of the SWP, and also district treasurer. This gave him access to the membership list, home addresses, contact phone numbers and a few bank accounts.

‘And of course it gave you justification on knocking on a door at any time to talk to anyone if you wanted to find anything out.’

Being district treasurer as opposed to just branch gave him justification for going further afield. He visited about three quarters of the Leyton / Leytonstone branch addresses. This included helping to recruit new members and reporting if they were disaffected members from other groups.

Why would all this information be wanted? According to Miller, knowing the size of the group was critical, it indicated the ‘virility’ of the organisation.

‘We were at the rawest end of just grabbing information and things like that. When it got entered into the machine… that turned around and gave it some assessment. We were just harvesting whatever we could and letting others analyse.’

Later he agrees that the Security Service (MI5) was interested in the sort of material he could provide, such as the lists of names of SWP members.

He resigned as district treasurer because there were internal issues in the group. Miller appears to have aligned with a faction in the SWP, though it is unclear what the political issue was, even to him at the time:

‘I resigned on the grounds that whoever it was resigned with me told me that I was going to have to resign because we were forming a different view.’

He wasn’t upset about losing his position because it was good to move on and because a ‘pretty fair picture had been gained.’

Miller was also on the social committee of the SWP’s Outer East London District, though he says that apparently involved ‘virtually nothing’ and he never arranged anything.

He also chaired branch meetings but claims this did not amount to much as so much of the agenda was centrally controlled. His managers were relaxed about him assuming these positions of responsibility. They didn’t directly instruct to do it, but said it was a good thing to do if he had the opportunity and thought it would work. Generally, he paints a picture of managers not being too fussed how he did the job as long as they got the information.

Miller accepts that he had some influence as a result of these positions, but says it was not huge and he could not have changed their perspectives on issues.

REVOLUTION

Asked about the SWP’s aim to have revolutionary change to create a socialist society, Miller said that nobody expected it to be any time soon.

‘They were far more interested in building the working class movement, in order to generate an attitude whereby a new society could be formed.’

He said, while there was talk of violence being likely in some eventual mass overthrowing of the current system, individual acts of violence were discouraged by the SWP.

As with other undercover officers, personal details were reported by Miller simply because they were available. The longer term view was that things like personal bank details may serve a policing purpose further down the line.

‘These individuals had been identified by Security Services as people who were worthy of watching and therefore “worthy of watching” means knowing where they are and how to get hold of them.’

Miller reported on a woman in the SWP, Madeleine, who he later deceived into a realtionship, initially updating the file which had already been opened on her.

SPYING ON CHILDREN

Some of Miller’s reports refer to children. There was no prohibition on this; it was ‘just more colour to the picture of the main target’. Asked if he would initiate opening a file on a child, Miller replied:

‘It depends on the age of the child… Certainly when you’re getting to 15 and 16-year olds, some of those would be considered if they were being sufficiently active to be worthy of a bit more attention.’

Pressed on this issue, he conceded that giving a child ‘a bit more attention’ did indeed mean opening a Special Branch file on them. Despite having just told us that people were watched because they’d been watched in the past, he tried to brush off spying on children as a harmless activity that was only done due to the inefficiencies of the filing system:

‘this was a hugely paper-driven system, and the fact that you opened a file actually reduced hugely the amount of paperwork that was involved. I mean, I won’t go into the huge filing processes, but it actually made everything a lot quicker and structures and that. So if somebody was constantly being referred to in all sorts of purposes, then they’d probably get a file number, purely and simply because it structured everything better.’

SUPPORT FROM MANAGEMENT

Miller is of the view that more professional advice could have been available to him. However, he recognises that he would have been determined to go his own path, and did not take advantage of what might have been available in any case.

After the deployment Miller left Special Branch to go into other forms of policing.

ALAN BOND – ANOTHER CHILD?

At the very end of the day’s questioning, Miller was asked about another officer, ‘Alan Bond‘ (HN67, 1981-86) and whether he had heard if Bond had relationships while undercover.

Miller and Bond’s wives were friends but it is only recently that Miller came to know that Bond had admitted to his wife he had a relationship while undercover. Miller did not confirm whether a child had been fathered out of this.

Written supplemented witness statement of Vince Miller

<<Previous UCPI Daily Report (11 May 2021, part 1)<<

>>Next UCPI Daily Report (12 May 2021)>>

Makes your blood run cold, even though we knew in theory at the time that this was happening. For example nit to discuss anything on the phone & hearing the click as the phone tap was put in