UCPI – Weekly Report 6: 4-7 May 2021

This summary covers the third week of the four-week 2021 hearings of the Undercover Policing Inquiry (UCPI), examining the Metropolitan Police’s secret undercover political policing unit, the Special Demonstration Squad, from 1973-82.

Witnesses from the police and the ‘non-State core participants’ gave evidence, and some witness statements from police who were unable, unwilling, or not called upon to appear personally were summarised. This follows the format of last week’s hearings, and many of the same topics were covered.

Rather than unfolding like a fictional courtroom drama, with revelations that suddenly turn the course of the narrative, the hearings of the UCPI are turning the wheel on a microscope to reveal more details about the events it is examining. We already have the big picture: the abusive activities of spycops in England and Wales 1973-–82. This week gave us many more details of those activities.

POLICE ARE ABOVE THE LAW

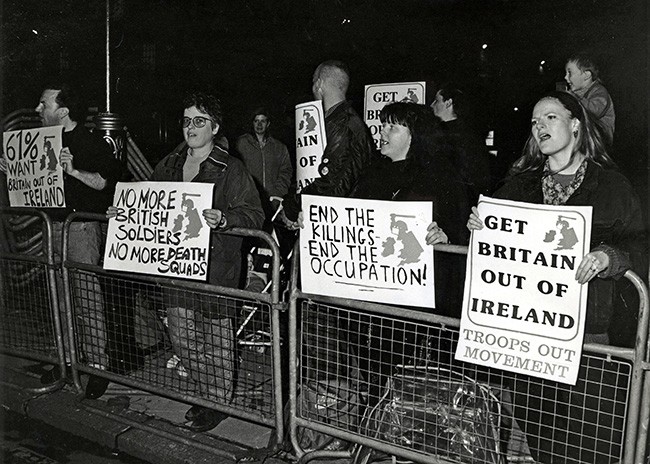

‘Mike Scott’ (HN298, deployed 1971-1976) gave one of the clearest statements yet that Special Demonstration Squad (SDS) undercovers considered themselves exempt from the laws they were supposed to uphold. In 1972, Scott was accused of being a police officer by Géry Lawless, an activist in several organisations focused on Northern Ireland issues which Scott had infiltrated.

Scott laughingly related how later that day, while driving around randomly, he somehow chanced upon Lawless when the latter was alone in a phone box. He cornered him there and after an exchange of words punched him so hard in the face that Scott chipped a bone in his hand.

When asked to justify his violent crime against a member of the public, Scott replied:

‘It was acceptable to me and I was the one that made the decision. I was the one that was there, and the person that was the so-called victim was Géry Lawless’.

The implication of ‘you deserve what you get because I say so’ is more text than subtext here.

POLITICIANS ARE NOT ABOVE THE LAW

Scott attended the Young Liberals’ 1972 annual conference in his capacity of Membership Secretary for their Putney branch. He reported on the presence of MP David Steel, directly contravening the ‘Wilson Doctrine’, which said that MPs should be told if they are subject to state surveillance.

According to Scott, ‘MPs are not above the law’. Spycops are apparently another matter, especially when punching people in the face.

Although Scott didn’t pick up a criminal record for his assault on Géry Lawless, he did for his actions during the Stop The Seventy Tour anti-apartheid campaign. He was convicted of obstructing a public highway under his fake identity, which was stolen from a living person.

SPYCOPS AUTHORISED TO LIE UNDER OATH

Scott’s lying under oath was authorised by his superiors, and he never gave a thought to whether the real Michael Scott now has a criminal record. In fact, he doesn’t even consider it in those terms:

‘What happened to me was not exactly a criminal record, it was really of no consequence, actually.’

In fact, he said, the identity theft, used to set up a bank account, might have been beneficial to the real Michael Scott because ‘my credit record was good.’

The unshakable conviction that whatever he chose to do was the best course of action simply because he chose to do it wass astonishingly clear. The Inquiry is now investigating whether the real Michael Peter Scott has a criminal record for this conviction.

Scott was not alone in being arrested, charged and convicted under a false identity. ‘Barry / Desmond Loader‘ (HN13, 1975-78) infiltrated the Communist Party of England (Marxist-Leninist) and was arrested twice while undercover. The first occasion, in late 1977, was for ‘insulting or threatening behaviour’ following a clash with the fascist National Front (NF) outside Barking police station.

Just three days after his court appearance for that, Loader was arrested a second time, again for clashing with the NF. Police records [MPS-0526784] reveal that Superintendent Ken Pryde established contact with a court official during the proceedings, giving them Loader’s cover name and his status as:

‘a valuable informant in the public order field whom we would wish to safeguard from a prison sentence should the occasion arise.’

Loader was found guilty, fined, and given a one-year bind-over of £100. It is noted in an SDS ‘Minute Sheet’ that this sentence was considered ‘very useful’ as it would allow Loader to keep a low profile for the remainder of his deployment [MPS-0526784].

LAWYER-CLIENT PRIVILEGE DIDN’T APPLY TO SPYCOPS

Naturally, the arrests and trials of spycops meant that the undercovers took part in meetings between the genuine activists and their lawyers. ‘Mike Scott’ was one of 14 people arrested in May 1972 for blockading a coach carrying the British Lions rugby team as they were leaving to play in apartheid South Africa.

Scott’s reports include comments from the activists’ lawyers. These have been redacted by the Inquiry as even now, 50 years later, they are subject to legal privilege. And yet, they were put in a report to the prosecution side from a spy among the defendants!

‘Geoff Wallace’ (HN296, 1975-78) infiltrated the International Socialists (IS). In April 1976, during their Right to Work Campaign, the IS newspaper Socialist Worker hired solicitors to represent those arrested while campaigning. Wallace reported [UCPI0000012323] on their meetings, likewise ignoring lawyer-client privilege.

This right, long protected in common law, is recognised by the European Convention on Human Rights, and can only be waived by the client. It is also recognised as absolute, in the sense that once privilege is established, it may not be weighed against any other countervailing public interest.

THE SDS MUST BE KEPT SECRET

Apparently, it’s a right that can be easily overridden by secret and secretive police units eager to avoid exposure and embarrassment. Discussion in the above mentioned Special Branch Minute Sheets reveals that Loader’s senior officers prioritised keeping his identity secret over any other consideration. Scott’s superiors did the same thing.

In 1979, spycop ‘Graham Coates’ (HN304, 1975-79) made ‘an error of judgement’ when, during a traffic stop, he gave a uniformed officer his real name but showed the driving license in his cover identity.

SDS boss Mike Ferguson (a former undercover himself) was ‘incandescent’, not just at Coates’ own indiscretion but at the potential revelation of the unit and its methods. Coates was withdrawn from the field on the spot.

In previous years, senior officers attempted to pass off incidents of criminal activity by spycops as ‘a few bad apples’ or used the ever-popular ‘rogue officer’ defence. Now, however, evidence continues to mount up of complete awareness by very senior officers. There was clearly a two-way flow of information between the SDS and MI5 – not only of requests to spy on people and the resulting reports, but also the criminal activity of the officers themselves.

THE MET COMMISSIONER KNEW

Sir Robert Mark, March 1977

Graham Coates, ‘Bob Stubbs’ (HN301, 1971-76), ‘Roger Harris’ (HN200, 1974-77), and other spycops described visits to the SDS ‘safe house’ from various Metropolitan Police Commissioners (the highest officer), Assistant Commissioners, Deputy Assistant Commissioners, and the Commander of Special Branch.

Coates recalls managers demanding ‘maximum attendance’ from all deployed spycops for a visit from then-Commissioner Sir Robert Mark – ironically renowned for his drives against police corruption.

This tallies with similar reports by spycops from the 1960s and 1990s. These visits seem an established part of the Met Commissioner’s role; at the very least, they show full awareness of the unit.

Coates also remembered a remark suggesting spycops’ expenses accounts were thoroughly examined by the Commissioner (even if reports might not have been). This shows an astonishing level of attention to detail for individual officers’ activities. Generally though, the purpose of these visits was to praise the undercovers and occasionally present them with bottles of whisky.

NOTHING WAS EVER DISCUSSED

When not entertaining senior police officials, the safe houses were used for meetings between spycops and their managers once or twice weekly. Two very different pictures of activities there emerged this week.

One is of a ‘social’ environment that somehow fails to include any discussion of what the people there spent most of their time doing. According to Scott, the twelve or so spycops never talked about their undercover work, the groups they infiltrated (even between spycops in the same group!), the activists they spied on, or the tactics used to get close to them.

This is the period during which the practice of stealing dead children’s identities as the basis for undercover personae begins and solidifies as required practice. There was some reluctance from a handful of spycops, but the idea, seemingly initially used by Scott, became management policy and was effectively enforced.

Other tradecraft also took shape in this era. Enough spycops have reported a lack of formal training, hands-off management, and the absence of a manual or even guidelines, making it unclear how tradecraft was developed and passed on if the undercovers themselves did not talk about it either.

In this picture presented by amnesiac officers, there were no spycops with (memorable) reputations as womanisers. Likewise, there was supposedly no way that management could have been aware of spycops having intimate relationships with female activists because this was never mentioned. In the hundreds of meetings that Scott attended, he has no memory of these things ever being spoken of. (He does remember chatting about toy soldiers though.)

SAFE HOUSE ‘BANTER’

The alternative picture is of a group of men letting off steam, comparing notes and exchanging ‘banter’. Coates and Harris both described officers who spoke so frequently and crudely about the women they had calculatedly deceived that managers would have been in no doubt about the nature of those relationships. Rather than being unaware of what was being discussed, managers participated in the ‘low-level communal humour’ that characterised the conversations.

Coates states that Richard Clark (‘Rick Gibson’ HN297, 1974-76) had a reputation for having sexual relationships. He also recalls that ‘Jim Pickford‘ (HN300, 1974-76) was widely known as a philanderer. This matches what’s known of these officers’ activities. A third officer, whose details he did not recall, also behaved in this way.

Asked about the kind of things being said, Coates reluctantly shared one example:

‘he’ll have made her bite the blankets again last night.’

The Inquiry also asked him an anecdote about a female activist who could lactate on demand. Although Coates has no recollection of this, the fact the Inquiry raised it also shows the type of conversation known to have taken place.

WHY THE LEFT BUT NOT THE RIGHT?

The spycops did not choose targets randomly. In the period under examination in the current Inquiry hearings, 1973-82, all groups spied on were left-wing. Officers were allowed to switch groups if they wanted to (Coates left the International Socialists because he was getting bored and thought the anarchist movement might bring more spark to his life). So why didn’t they do so when it became obvious the groups were mostly harmless?

This week’s evidence only consolidates the emerging picture of spycops infiltrating small groups with either completely peaceful and democratic methods and aims, or no capacity to carry out any really disruptive or violent action – even if it was suggested.

Again and again, the spycops demonstrate the ability to believe they reported nothing of real use from spying on groups that were harmless, whilst simultaneously also believing they contributed significantly to preserving the safety of the realm, that the money enabling them to do so well-spent and their actions were completely justified. It’s a positive symphony of cognitive dissonance.

As mentioned in our previous weekly report, during this period the right wing were on the rise. Openly fascist and racist groups were using tactics such as firebombing, burning down businesses owned by Black and Asian people, and holding meetings in diverse areas to deliberately bait the residents. Yet these groups were never – with one exception – infiltrated.

That exception came about by accident. The Workers Revolutionary Party was so concerned about the National Front that they asked one of their members to infiltrate it. Ironically, that member was SDS undercover ‘Peter Collins’ (HN303, 1973-77).

Had the NF realised that they had been deceived, it is likely that they would have responded with violence; the question of whether being exposed as a spycop or being exposed as an activist would be more dangerous is an interesting one.

UNDERMINING GROUPS WORKING FOR EQUALITY

Although the left-wing were very aware of the problems caused by the right-wing, which was a genuine threat to public order with subversive intentions, the police were apparently oblivious.

Scott claims that:

‘There weren’t any right-wing groups who were demonstrating, or causing any problems as far as I can recall, at the time.’

He and almost all of his colleagues infiltrated anti-fascist groups – why were these so prolific if right-wing groups were not a problem?

They clearly were, and the spycops unquestionably had the freedom and the remit – preserving public order – to infiltrate them, if they chose to. The fact that they didn’t indicates that the SDS was a unit dedicated to undermining and spying on groups working for a more, rather than less, equal society.

We know there was systemic sexism permeating the SDS, which, according to Coates, viewed the women’s liberation movement as:

‘a bunch of angry women that could be ignored.’

It is not much of a stretch to speculate that systemic racism went along with it. It is very disturbing that these attitudes are still present today.

Worryingly, an isolated incident of International Socialists reported as attacking people at the NF offices with stones and bricks was seized upon by the Inquiry:

‘We note that, if the report is accurate, this was an occasion on which the violence was started by left-wing activists from the infiltrated group.’

This is not the first time that the Inquiry has used reports of ‘violent’ anti-fascist protests as a justification for many of the deployments.

In contrast, an SDS report dated 7 March 1977 [UCPI0000017776] describes a single coach of members of the Socialist Workers Party (as the International Socialists had become) being attacked by five coaches of National Front supporters at Watford Gap Service station.

For some reason, the Inquiry glosses this incident in neutral terms:

‘The SWP contingent from NW London and West Middlesex districts appears to have been involved in an encounter with the National Front in a service station en route to Birmingham’

This gives a misleading impression of this serious and unprovoked attack by the NF on SWP members.

UNWILLINGNESS TO ACCEPT CULPABILITY

Blair Peach

A deeply upsetting example of State unwillingness to accept culpability for its role on the wrong side of history came directly from the Inquiry’s Chair, Sir John Mitting.

During the Undercover Policing Inquiry’s hearing on 23 April 2021, which was the 42nd anniversary of Blair Peach’s death at the hands of police as established by the Met’s own report, a minute’s silence was held for the murdered teacher. In his introductory remarks for the Mitting referred merely to Peach being killed by ‘a blow to the head’. He did not mention the police at all.

Celia Stubbs, who was Blair Peach’s partner at the time of his death, spelled out how the rise of the right wing was a growing problem during the years covered by this phase of the Inquiry. She and Peach were members of the Anti-Nazi League from its formation in 1977. Two years later, when a call went out from the multicultural community of Southall for support against the NF, they responded.

The NF were ‘campaigning’ in Southall in April 1979 in the run-up to the general election, despite their candidate not living there. Holding rallies in areas with large Black and Asian populations was a common NF tactic. They were met with counter-demonstrations by exactly the kind of groups – including undercovers – that the SDS had been focused on infiltrating for the last decade.

For example, at one such event in 1977, which became known as the Battle of Lewisham, at least 18 spycops were present and over 50 pages of reports were produced. Nobody died at the Battle of Lewisham. In contrast, the 1979 counter-demonstration that Blair Peach was killed at in Southall was supposedly only attended by one spycop.

A BLENDED, ‘GISTED’ DOCUMENT

Celia Stubbs knows that one of the spycops attended the demo in Southall that day. The Inquiry has taken evidence in secret from officers who it does not want to identify. It has then blended their testimony into a single ‘gisted’ document. In it, an officer says they were at the demonstration in Southall, saw violence and being horrified left before Peach was killed.

Celia Stubbs, 2021

Stubbs is offended by all of this. Firstly, the total secrecy around the officer – we aren’t given their name, cover name, or any other details at all. Secondly, the idea that there was only one spycop at the demo is ridiculous.

There was a large presence from the Socialist Workers Party, the most infiltrated group in the history of the SDS. Following the call-out from Southall residents, it is unthinkable that spycops eager to maintain their cover would not have been there in large numbers.

Not only that, but the demonstration was a left-wing response to obvious baiting by the right-wing NF. It was blatantly going to turn into a public order issue. This was finally something that legitimately fell within the remit of the SDS. Yet they maintain that only one officer was present, and he left early – precisely because there was public disorder!

The killing of Blair Peach is heart-breaking, and also terrifying in that it could happen to anyone, on any demonstration, not just against fascism. His final hours, the cover-up of the cause of death, and the subsequent fight for justice, are covered in more detail elsewhere.

Celia Stubbs talked calmly, but with obvious strong emotion, about Blair’s death and the events that followed, including the banding-together of groups campaigning for justice for those killed by police.

Simultaneously, it was the beginning of spying on those groups. The solidarity of grieving families was considered a subversive act.

Stubbs said:

‘It’s obvious that when someone is killed, the police don’t want to be associated with it. This looks like yet another cover-up. It makes us feel like we’re not being heard…

‘I mean, Blair was killed by police officers and our feelings and campaigns were criminalised. The police, I think, wanted to keep ahead of our campaign so that Blair’s killers… we were never able to hold them to account.’

Stubbs said that, despite having seen so many secret police reports, she is left with as many questions as she had before. One of these reports [MPS-0001219] was from decades later. It was written in the summer of 1998, regarding plans to commemorate the 20th anniversary of Blair Peach’s killing.

Stubbs told the Inquiry that an officer referred to in the report was Mark Jenner (‘Mark Cassidy’ HN15, 1995-2000) who infiltrated the Hackney Community Defence Association and the Colin Roach Centre (also in Hackney). Whilst undercover he deceived an activist, ‘Alison‘, into a long-term relationship.

Cassidy reported that:

‘local trade unions are organising a large rally and demonstration, which will be presented with a strong anti-racist/anti-police flavour… the event will inevitably attract a large left wing presence with particular accent on anti-police type groups and the potential for disorder will be significant.’

Stubbs was indignant at this:

‘we’d had remembrance demonstrations after five years, after ten years, and this was twenty years. There’d never been any disorder. I don’t know why he put that. I think it’s pretty unpleasant.’

This continues a long-running tradition of spycops exaggerating the potential for disorder when making reports on groups and why they had to be reported on.

NO THREAT TOO SMALL, NO GROUP TOO HARMLESS

The spycops were trusted to use their intelligence to discern threat levels, yet were apparently unable to tell the difference between fanciful ideas (e.g. the Workers Revolutionary Party finding enough people to infiltrate and subvert every single branch of the Labour Party Young Socialists) and genuinely executable plans (like having a skip delivered to a hotel).

An SDS report dated 26 May 1977 [UCPI0000017437] describes a member of the SWP announcing that he was mobilising local trades union branches to support an anti-Jubilee demonstration during the visit of Princess Anne to Kensington Town Hall on 31 May, and of 1,500 expected demonstrators, 1,000 of whom were likely to be trade unionists ‘violently opposed’ to Jubilee celebrations. This seems wildly and obviously far-fetched.

Additionally, the small groups most often spied on usually didn’t manage to carry off their most outrageous genuine plans, such as painting lines on small roads to show the path of a new motorway.

Some groups, such as the Workers Revolutionary Party and the Socialist Workers Party, regarded by the SDS as ‘subversive’ – that is, wanting to overthrow parliamentary democracy – entered candidates in elections. If they were seeking to overturn Parliament, then legitimately being elected to it is surely the least subversive way of doing so.

Many of the groups had democratic internal processes, something that the spycops were blatantly aware of given how many of them were democratically elected to positions of influence within those groups.

ACCESS TO PERSONAL DETAILS

The spycops’ stories vary as to whether or not they were given guidance on whether or not to take formal posts in organisations they infiltrated. Enough of them did so, with full knowledge of their managers, that it was obviously accepted.

Positions such as treasurer and recruitment officer gave them access to personal details of all group members. Often, they were part of the vetting process and point of first contact for people interested in joining. This gave them influence over the actual makeup and structure of the groups, and to some degree taking on these tasks would have also compensated for their lack of genuine activism.

As is notable from the accusation that caused Mike Scott to assault Géry Lawless, some groups were suspicious that newcomers might be undercover cops.

After Rick Gibson’s exposure by Big Flame, some members talked about how he had badly messed up his turn to give a talk on activism. Lack of background, political awareness, and genuine interest in activism were sufficient red flags that some spycops compensated for by deceiving activists into sexual relationships. To form a relationship with an established, trusted member of a group encourages members to extend their trust to the spycop.

This would almost certainly have been seen as easier than researching the philosophies of the groups and differences from other groups on the left. Coates had to give a 20-minute talk on the history of the Labour Party to the IS group he was infiltrating, so this was not unique to Big Flame. The spycops were trained to ‘mirror’ their targets, but it’s impossible to do so if you’re the only one talking.

NOT JUST INFLUENCING, BUT CREATING GROUPS

Richard Clark (‘Rick Gibson’ HN297, 1974-76) was the spycop responsible for the formation of the South East London branch of the Troops Out Movement. His rise through the ranks to the top of the organisation, and eventual bid to join Big Flame, was achieved by deceiving four women activists into sexual relationships, and manipulating and betraying the members of both groups.

More details can be found in last week’s reports, and in the opening statement on behalf of ‘Mary’, one of the women, and Richard Chessum – who provided his own written witness statement as well.

More details can be found in last week’s reports, and in the opening statement on behalf of ‘Mary’, one of the women, and Richard Chessum – who provided his own written witness statement as well.

Chessum knew about Gibson’s sexual relationships, and says it was general knowledge at the time. Did Gibson accidentally tell different women different things, and they then compared notes and spotted the discrepancies in his cover story? ‘Mary’ said he didn’t share any contact details with her, was often very hard to reach, and she knew very little about his background.

Having thoroughly investigated Gibson, Big Flame took action. They invited him to meet them in a pub and then spread out all the evidence they had gathered. ‘He looked as though he was going to cry’, said Chessum, who was told about it at the time.

Gibson came up with one last story and gave them a phone number of the office where his brother was supposed to work. It was another lie. When they went to check his flat, they found it empty, Gibson having had done a midnight flit.

After this, Chessum met with Mary and her flatmate, and told them what he had seen. He says they were shocked but not surprised. They had already discussed the possibility of Gibson being some kind of police officer. They had noticed his habit of never staying overnight, and wondered if this was because he had a wife to go back to.

BREAKING APART FAMILIES

Because, of course, the spycops did have wives to go back to. ‘Graham Coates’ (HN304, 1975-79), who spoke for all of the 7 May hearing of the Inquiry, said that on joining the SDS he was specifically asked if he was married or in a stable relationship:

‘It was explained… in very general terms that they felt that an officer in a stable relationship or a stable married relationship would be a more stable character, given the likely exposure to stresses and strains of the likely work involved.’

There appears to have been no thought whatsoever given to the stresses and strains on the families themselves. Once again, women were exploited for the benefit of the SDS.

‘Jimmy Pickford‘ (HN300, 1974-77) infiltrated a number of groups, including anarchist ones, like the South London branches of the Anarchist Workers Association and the Federation of London Anarchist Groups.

His widow provided a statement describing how she was given no support during his absences, and had to take great pains to protect his cover whilst trying to raise their two small children, effectively as a single parent. There was no going to joint social gatherings or having friends round to their home. This left her extremely isolated, as she had no family in the UK and so was reliant for support on close friends.

In fact, the majority of the marriages relied upon by management to keep the spycops stable disintegrated soon after their deployment ended. Despite there having been ample opportunity since the unit was set up, there was no kind of post-undercover care in place for the families and the spycops themselves.

The spycops seem to have been as oblivious to the damage they were doing to the people and causes they spied on as they were to the damage they were doing to their own families.