UCPI Daily Report, 17 Nov 2020

Tranche 1, Phase 1, Day 12

17 November 2020

Opening statement from Dave Smith

Witness hearings procedural meeting

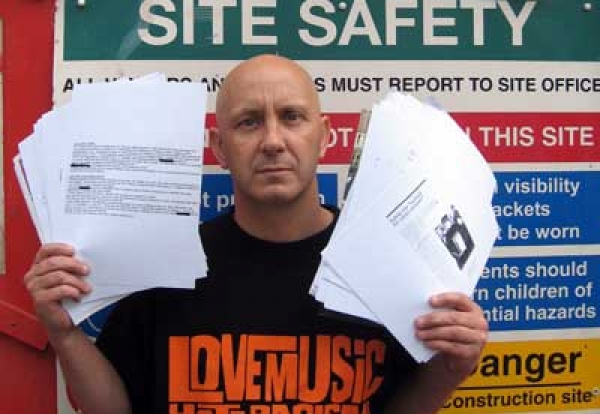

Dave Smith with his blacklist file

Tuesday 17 November was scheduled to be a day off for the Undercover Policing Inquiry, but two items pushed their way onto the schedule.

Dave Smith, blacklisted trade unionist and core participant at the Inquiry, was due to give his opening statement along with everyone else last week. However, it was dramatically withdrawn after a legal challenge to its contents; specifically, that he was going to give the real name of one of the spycops who spied on him, Carlo Soracchi. This came even though the name has been in the public domain for 18 months and you just read it at the end of the previous sentence.

This led to anyone referring to Soracchi (real name of SDS undercover ‘Carlo Neri’) at the Inquiry having to promise not to say his actual name. After that was sorted out, Smith contracted Covid so had a further few days’ delay until today.

The other matter was a meeting of the barristers representing the various core participants at the Inquiry – police and those that were spied on – about the format of questioning witnesses. It followed a couple of grumpy exchanges between the Chair and Rajiv Menon QC, who represents non-state core participants, including the one where Mitting threatened Menon with being silenced.

Dave Smith

Blacklisted trade unionist

Smith explained that he spoke on behalf of the Blacklist Support Group (BSG), representing union members who were unlawfully blacklisted by major construction firms.

When the BSG first spoke about being blacklisted for union activities, they were ignored by the authorities and ridiculed as conspiracy theorists. But it isn’t a conspiracy theory, it’s conspiracy fact – and it involves the collusion of the police and the security services.

TRADE UNIONS HAVE ALWAYS BEEN BLACKLISTED

Trade unions arose during time of the industrial revolution and British Empire, Smith said. As dynastic fortunes were made in the slave trade, Parliament – an institution then comprised solely of the very wealthy – was passing the Combinations Acts to make trade unions illegal.

State agents have spied on working class organisation ever since. Hostility towards trade unions – just like racism and sexism – became so deeply ingrained in the mindset of the British establishment that it has carried on through the generations.

In 1834, year of the Tolpuddle Martyrs, a meeting of the Master Builders in London agreed that every craftsman wanting work had to sign ‘the document’, a declaration that they would never join a trade union. Failure to sign meant dismissal or refusal of work which, in turn, meant destitution.

In 1919, a group of Conservative MPs, captains of industry, and ex-military intelligence officers set up the Economic League, ‘a crusade for capitalism’, keeping left wing union activists under surveillance and out of work. They had direct formal and informal links with police and MI5. Thousands of workers lost work.

THE CONSULTING ASSOCIATION

The Undercover Policing Inquiry will find that, after the Economic League closed down in 1993, Cullum McAlpine, director of Sir Robert McAlpine Ltd, bought the construction part of the Economic League’s blacklist to set up The Consulting Association.

This secret body was comprised of major construction companies including: Balfour Beatty, Laing O’Rourke, Costain, Skanska, Kier, Bam, Vinci, AMEC and AMEY. Between them, they illegally orchestrated the blacklisting of construction workers.

The Consulting Association was run by former Economic League employee, Ian Kerr. The Information Commissioner’s Office raided it in 2009, seizing files on 3,213 people. Details in the files included not only names, addresses and National Insurance numbers, but photos, phone numbers, car registrations, and information about the subject’s medical history and family members.

When a blacklisted worker was elected as a union representative, or when they raised concerns about safety on site, submitted an employment tribunal or took part in a protest, it was recorded on their Consulting Association blacklist file.

The Consulting Association didn’t have spies everywhere. Instead, construction companies nominated a contact, usually a director, who received information from managers on site and forwarded it to Ian Kerr.

INDUSTRIAL SCALE INDUSTRIAL BLACKLISTING

Every job applicant on major building projects had their name checked against the Consulting Association blacklist. If there was a match, the worker would be refused work or dismissed.

Each blacklisting name-check cost £2.20. The last set of invoices for Sir Robert McAlpine alone, when the company was building the Olympic Stadium, was for £28,000. This isn’t a few managers chatting after work, it’s industrial-scale, systematic blacklisting of union activists.

Because of blacklisting, in the middle of the 1990s building boom there were highly qualified and experienced workers who found themselves virtually unemployable. While many construction workers took their families on holidays, blacklisted workers defaulted on their mortgages.

THE HUMAN COST

Partners of blacklisted workers had to take two or three jobs to keep the family afloat. One wife of a blacklisted worker has spoken about the painful decision not to have a second child because of the family’s financial hardship. Families lost their homes and there were divorces.

Smith described how, in the 1990s he was a worker and trade union safety representative on the Jubilee Line Extension. Some of his fellow workers who took part in a safety dispute over the lack of fire alarms at London Bridge station ended up being blacklisted.

Blacklisted workers outside the High Court

Some of those workers went on to take their own lives. No one can say that blacklisting was the sole reason for any suicide, but prolonged periods of unemployment and family tensions are not good for anyone’s mental health. Blacklisting has contributed to deaths.

Blacklisting causes workers’ deaths in other ways. When union safety reps are sacked for highlighting unsafe conditions such as asbestos, electrical safety or poor scaffolding, it sends a message to other workers and creates a climate of fear where they’re too scared to report concerns.

As a result, the blacklisting of safety reps is a factor in workplace fatality rates in the construction industry – consistently the sector with the highest number of deaths of any major industry in the UK.

Parliament was so outraged by The Consulting Association that it introduced the Blacklisting Regulations 2010. In 2016, a High Court case was settled when the UK’s biggest building firms made a public apology and paid damages for their blacklisting activities.

SPYCOPS BREAK THE LAW

But the Undercover Policing Inquiry will find that it wasn’t just the major firms who kept union activists under surveillance and contributed to blacklisting – it was the same political police who are at the heart of the Inquiry.

The police’s internal spycops investigation, Operation Herne, produced a report on blacklisting which said:

‘Police, including Special Branches and the Security Services, supplied information to the blacklist funded by the country’s major construction firms, The Consulting Association’

The police investigation found that, prior to The Consulting Association’s foundation in the 1990s:

‘Special Branches throughout the UK had direct contact with the Economic League, public authorities, private industry and trade unions.’

The Undercover Policing Inquiry has already seen that, from the start of the Special Demonstration Squad (SDS) in 1968, spying on left-wing trade union activists was a central part of the unit’s activities.

Special Branch files were effectively a database for MI5, private firms and others to find out about trade union activists. Indeed, many trade unions had their own dedicated Special Branch files.

SPECIAL BRANCH INDUSTRIAL UNIT

The Special Branch Industrial Unit was established in 1970, just two years after the SDS, ‘with the aim of monitoring trade unionists from teaching to the docks’ and developing a network of industry contacts that included company directors, as well as General Secretaries of trade unions.

The police’s Operation Herne report said the Special Branch Industrial Unit had a dedicated officer as official liaison with Economic League. Industry informers had two-way sharing of info with Special Branch’s Industrial Unit. Intelligence gathered by both undercover and uniformed officers was available to the Industrial Unit and was passed on to both major employers and blacklisting organisations.

SDS spycops often worked for the Industrial Unit, before or after being deployed undercover. One was HN336, who told us yesterday that Chief Superintendent Herbert Guy ‘Bert’ Lawrenson, head of the Metropolitan Police Special Branch’s C Squad in the SDS’s early days, went to work for the Economic League.

For all its admissions, Operation Herne didn’t even mention Lawrenson. Blacklisted workers expect the Inquiry to examine the relationship between officers from the Special Branch Industrial Unit and their former boss, the man who quite possibly hired & trained them, Bert Lawrenson.

SPYCOPS DATABASE

As well as Special Branch files, police intelligence on political activists was kept on the National Domestic Extremism Database (NDED), originally compiled by the National Public Order Intelligence Unit (NPOIU), a sister unit to the SDS and one of the main topics of the Inquiry.

This database holds information on thousands of citizens who the State considers ‘domestic extremists’, many of whom have committed no crime whatsoever. Another unit responsible for the database was the National Extremism Tactical Coordination Unit (NETCU).

Superintendent Steve Pearl, NETCU’s former head, told the Daily Telegraph that the unit was set up to:

‘take over MI5’s covert role watching groups such as the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament, trade-union activists and left-wing journalists’.

The Consulting Association constitution required companies to send a director to secret quarterly meetings.

In October 2008, Detective Chief Inspector Gordon Mills of NETCU gave a presentation to a secret Consulting Association meeting that included eight senior managers from blacklisting firms. He told them of ‘emerging threats’ from the left wing, for which ‘companies needed to have strong vetting procedures in place’. Bear in mind that this was a police officer helping the Consulting Association, a company whose work was illegal.

In a witness statement compiled for the High Court blacklisting trial, Ian Kerr, Consulting Association CEO, said that NETCU:

‘wanted an output for their information… I gave them the email addresses of the contacts in the construction industry and they would feed them information’

NETCU and the Special Branch Industrial Unit, along with all the spycops units, are now absorbed into the Met’s Counter Terrorism Command. State spying on unions is now classified as counter-terrorism!

Sharing of police intelligence across all sectors of industry continues through Operation Fairway and the National Domestic Extremism and Disorder Intelligence Unit’s Industrial Liaison section. In 2010, the National Coordinator for Special Branch urged police forces across the UK to become ‘more proactive’ in putting on Special Branch briefings, to share information with academics and contacts in business and the public sector.

Special Branch clearly know that when they tell an employer someone is on a database of extremists, it will affect lives. It is the only possible result – and, therefore, the only real purpose – of their sharing information on trade unionists.

PERSONAL SPYCOPS

Smith then focused on a small group of union activists on the blacklist of which he was part. From the early 1990s until mid 2000s, they were spied on by three separate SDS officers: Peter Francis, Mark Jenner and Carlo Soracchi.

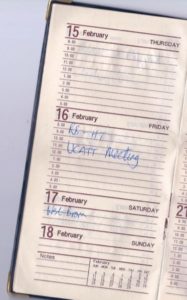

Page from undercover officer Mark Jenner’s 1996 diary, showing his attendance at a UCATT meeting

Mark Jenner infiltrated the construction union UCATT as ‘Mark Cassidy’. Claiming to be a joiner, he attended Hackney Branch of UCATT, and his union subscriptions were paid by a bank account set up by Special Branch.

In his undercover role, Jenner attended picket lines, protests, meetings and conferences. After each meeting, his partner recalled him at their shared home typing up pages of handwritten notes, presumably to be fed back to Special Branch as intelligence reports.

Jenner also infiltrated the Colin Roach Centre, which was home to Hackney Trade Union Resource Centre, and two small union groups in which Jenner actively inveigled himself; the Building Workers Safety Campaign and the Brian Higgins Defence Campaign.

Jenner actually chaired meetings and used his position as ‘a worker fighting for safety at work’ to contact union branch secretaries from unions including UCATT, UNISON, TGWU, RMT, EPIU, NUT and CPSA.

He wrote letters to safety body London Hazards Centre, and to INQUEST, the charity that supports people campaigning over deaths in police custody. Brian Higgins and John Jones were leaders of groups Jenner infiltrated, and both have entries on their blacklist files relating to those campaigns.

Smith personally remembers Jenner being particularly disruptive at meetings they both attended in Conway Hall, London. While spying on picket lines over unpaid wages at Waterloo, Jenner also came into contact and spied on other people, some of whom are now core participants in the Undercover Policing Inquiry.

One of these is Steve Hedley, currently Senior Assistant General Secretary of the RMT rail union. In the 1990s, Hedley was in a union delegation to Northern Ireland as part of the peace process organised by the Hackney Trade Union Resource Centre and the Colin Roach Centre. Mark Jenner was also part of that delegation and stayed at Hedley’s family home during the trip.

ANTI-FASCIST & PROUD

The trade union movement is proud of opposing fascism. At the time of spycops Peter Francis, Carlo Soracchi and Mark Jenner’s deployments, fascists were terrorising communities, planting bombs and committing racist murders. They also targeted union offices.

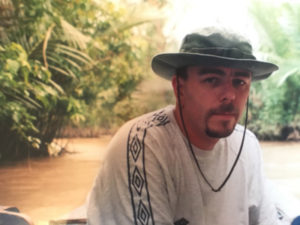

SDS officer Mark Jenner

Construction union activists stewarded labour movement events to protect them from fascist thugs. One loose network, of which Smith was a part, who did this was known as the ‘Away Team’. Spycops Peter Francis, Mark Jenner and Carlo Soracchi all spied on them.

Smith flatly accuses Mark Jenner, and through him the British State, of interfering with the internal democratic processes of an independent trade union. They did it by covertly joining the union UCATT, participating in debates and voting at meetings on policy motions; by distributing literature favouring a particular candidate; by calling for the sacking of an elected union convener; and by creating divisions.

Jenner also deceived ‘Alison’, an activist for the National Union of Teachers, into a five year co-habiting relationship during his deployment (Her account of this was heard on Day 6). Misogynist abuse of women activists is one of the most disgraceful human rights violations of the whole spycops scandal.

CARLO SORACCHI

When Jenner’s deployment was coming to an end, another spycops officer, Carlo Soracchi, using the name ‘Carlo Neri’ was sent to spy on the same group of activists.

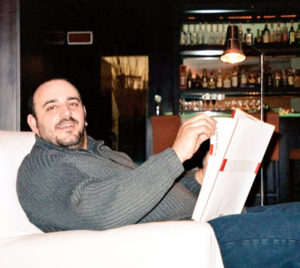

SDS officer Carlo Soracchi

On more than one occasion, Soracchi incited Frank Smith, Dan Gilman and Joe Batty to fire bomb a charity shop in North London. Joe Batty was a TGWU union steward. He has been denied core participant status by the Inquiry.

Soracchi claimed the shop in question was run by Roberto Fiore, leader of Italian fascist party Forza Nuova. Fiore fled Italy while being wanted by Italian police in connection with the terrorist bombing of Bologna railway station in 1980 that killed 85 people.

Smith accuses Carlo Soracchi of being an agent provocateur, of deliberately attempting to entrap union members by inciting them to commit arson. The spied-upon activists wanted nothing to do with the idea: they are trade union and anti-fascist activists, not terrorists.

Soracchi also deceived a Transport and General Workers Union rep from a homelessness charity, Donna McLean, into a relationship. She was one of two women he targeted for a relationship, the other being ‘Lindsey’.

Soracchi, having orchestrated a split from Donna, then moved in with Steve Hedley as a lodger. In October 2004, Hedley was victimised and sacked from the Channel Tunnel Rail Link project, a dispute that appears on his blacklisting file. Soracchi turned up on the picket line, spying on union members while supposedly showing solidarity with Hedley.

Smith mused on the bizarre fact that he was prohibited from saying Carlo Soracchi’s real name in this statement. He’s known it for over five years. When he published the book Blacklisted: The Secret War Between Big Business & Union Activists in 2016, he opted not to use Soracchi’s real name.

However, it’s now been in the public domain for 18 months. Four weeks ago Smith had an article published in Tribune in which he referred to Soracchi’s incitement to commit arson, using his real name.

It’s another one of the topsy-turvy aspects of the Inquiry that it, as the body charged with uncovering the truth about spycops, is the one place that we can’t say the spycop’s name.

PETER FRANCIS

Spycops did not merely spy on trade unionists: the intelligence they gathered was passed on to employers and found its way onto the blacklists.

SDS officer Peter Francis

Former spycop Peter Francis admits opening the Special Branch file on Frank Smith in the early 1990s. It included entries about his anti-racist role in the Away Team and his relationship with an American woman, Lisa Teuscher.

Francis says the blacklist file on Frank Smith uses his appraisal and almost his exact words: ‘under constant watch officially and seen as politically dangerous’. It’s laughable to suggest a construction manager could be the source of that.

Francis also gathered intelligence on Lisa Teuscher, primarily because of her role in the anti-racist campaign group Youth Against Racism in Europe. Spycops had her refused Indefinite Leave To Remain in the UK. She has a blacklist file, despite not working in construction at all.

SYSTEMATIC SHARING

No-one is suggesting spycops personally provided info to the blacklist. That was not their job. It was more senior officers from the Special Branch Industrial Unit or NETCU who were tasked with sharing information with ‘industry contacts’.

Another glaring example of information being fed to The Consulting Association blacklist from Special Branch relates to an incident in November 1999. Every Remembrance Day, the fascist National Front lay a wreath at the Cenotaph. That year, Frank Smith, Dan Gilman and Steve Hedley were there at a counter-demonstration.

Operation Herne has confirmed that the three core participants were observed by police on the day and that intelligence about their participation at the Cenotaph was added to Special Branch files. Within a few days, the same information appears on the blacklist, marked as supplied by Costain.

Two senior Costain managers are known to have had close relationships with Special Branch spycops: Dudley Barrett (now retired) and Gayle Burton (currently a senior executive at the Jockey Club).

If the purpose of the spycop units was genuinely, as the police claim, to detect serious criminality or public disorder, why, in over ten years of spying, were none of these people ever charged or prosecuted with a serious criminal offence? This is nothing to do with disorder or crime, it’s purely political policing.

Smith made another accusation: that the Special Branch Industrial Unit and NETCU supplied information to the blacklist.

PARTISAN POLICING

Despite what the police claim, they are not neutral. The State is never neutral in a major dispute between big business and trade unions. Police collusion in blacklisting is not an aberration, or the actions of a rogue unit, it is standard operating procedures for political police.

Seven million people in the UK are members of trade unions. And the unions are simply their members, rather than something separate. To spy on any union members or officials is to spy on the union as a whole. Those seven million deserve to know which of their branches were spied on, and which reps weren’t who they thought they were.

We want the names of the trade unions and all of the 1,000+ political groups that were reported on by the spycops to be released. But we want much more than that. We want the names of the contacts, and the companies that were provided with information about union members.

BLACKLISTING BEYOND CONSTRUCTION

We have found the construction industry’s blacklist, but clearly other industries have their own versions. The BBC kept a Staff Transfer Register (of those vetted by MI5). The Subversion in Public Life database, run by the security services, was used to blacklist civil servants. The retail sector’s National Staff Dismissal Register blacklist was actually funded by a £1million grant from the Home Office!

The 2002 BBC documentary True Spies featured an undercover officer explaining that Ford’s Halewood factory in Liverpool provided Special Branch with a list of all job applicants to vet. One of the spycops featured in it stated:

‘It was very, very important that trade unions were monitored… We were expected to check these lists. You call it blacklisting and that’s what it is. In any war there are always going to be casualties’.

PRIVATISATION OF STATE SPYING

Assistant Chief Constable Anton Setchell was the officer in charge of the UK police ‘domestic extremism’ spycops between 2004 and 2010. He is currently head of global security at Laing O’Rourke, one of the construction firms who worked with spycops to create and maintain the blacklist.

Superintendent Steve Pearl, who ran NETCU, is now a non-executive director at Agenda Security Services. Barrie Gane, the former deputy head of MI6, sits on the Board of Threat Response International. Both companies report on activists for corporate clients.

Control Risks, a private security firm that employs ex-State spies, had a £59,000 contract with Crossrail to keep union activists under surveillance. Those spied on included Frank Morris, first union rep on the publicly funded project, who was sacked within days of being elected.

Given the mass privatisation over the past four decades, has there been a blurring of the lines between State and corporate spying? Which companies got contracts? How much taxpayers’ money have they been given? If State spying is now privatised, what oversight is there?

WE UNCOVERED THE TRUTH

Smith said that the Blacklist Support Group is extremely sceptical about the Undercover Policing Inquiry’s chances of success. Everything we know so far about the spycops scandal in relation to trade unions and blacklisting is known because activists have uncovered it.

Steve Acheson has one of the largest blacklist files in the country and was almost unemployable for nearly a decade, nearly losing his home. It is people like Steve who have helped uncover the truth – not the police.

When the Blacklist Support Group first complained about police involvement in blacklisting in 2012, the Metropolitan Police refused to even accept the complaint! After lawyers got the complaint accepted, the Independent Police Complaints Commission, confirmed that:

‘it is likely that all Special Branches were involved in providing information about prospective employees.’

NETCU, a spycops unit that operated for seven years, now claims that all their files have been destroyed, and not a single page still exists. That is a blatant lie. Not only must their files still exist, I imagine they’re still being accessed.

As the Hillsborough families, the wrongly imprisoned striking miners, the Birmingham 6, and so many others can attest, it’s not name-calling to say police are capable of lying. So why do the police get the benefit of the doubt?

As recently as 2018, the police were telling us, and the Inquiry, that only one spycops officer had joined a union. It was clear then that this was nonsense. Any officer spying on unions without being a member would have stuck out a mile. They’re still lying to us.

We want our police files. But the police say they ‘neither confirm nor deny’ that they have such a file, due to national security.

TRUTH DENIED

In July 2018, the Blacklist Support Group held a meeting with Inquiry team, and specifically requested the release of police files on Brian Higgins and John Jones. This was because those two core participants were both severely ill and in their 70s.

Brian Higgins (left) on a UCATT picket

The BSG was given assurances by the Chair of the Inquiry, Sir John Mitting, that everything possible would be done to make this disclosure happen. More than two years later, the files have still not been released. Brian has died.

What possible national security reason can there be for denying a dying man access to his police file from the 1990s? Brian Higgins’ family are outraged at their treatment by the Inquiry.

The Inquiry is relying on reports from the police’s internal investigation, Operation Herne, yet they are selective, partisan publications. What’s striking is their use of language. They qualify terms, such as ‘alleged victimisation’ and ‘supposed blacklisting’, even though they had cast-iron proof in their own files.

There are 74 appendices to Operation Herne’s report – including witness statements with the former Special Branch contact with the Economic League – none of which have been disclosed to the Blacklist Support Group.

The Herne officers called Smith’s book, ‘Blacklisted’, ‘the most comprehensive collection of material on the subject’, a fact that demonstrates the need for accounts from activists who have uncovered the truth to be treated by the Inquiry with as much, if not more, validity as witness statements from the officers.

The 1968-72 spycops’ annual reports that have been published by the Inquiry should be seen for what they are: PR exercises for their bosses. The Inquiry must stop taking police documents as objective.

LIES, DELAYS & EXCLUSION

Rather than being transparent and accessible, the Inquiry has set up as many barriers as possible to prevent core participants, the public and the media from being able to view or listen to proceedings. Seeing the oral evidence is only possible for 60 people who have pre-registered, who must then travel to London during a lockdown to sit in a windowless, unventilated room and watch the proceedings on a TV screen.

The only other way to view evidence is via a transcript feed, which is like being transported back to the 1980s to watch it on Ceefax. This just doesn’t work. People get their news from the media, and the Inquiry’s system makes it impossible for journalists to check quotes which, in turn, means they can’t post reports in time for the TV and radio news.

BBC reporter Dominic Casciani said:

‘from a practical perspective as a working reporter, a public inquiry becomes largely impossible to report’

At the start of each day, the Chair states that:

‘members of the public are entitled to hear the same public evidence as I will hear and to reach your own conclusions about it.’

This is patently not true. Though it’s easily resolvable. The Inquiry could live-stream all of the evidence, exactly as the Grenfell public inquiry is doing. Unfortunately there seems little chance of this, and we seem to be watching a good old-fashioned Establishment cover-up take place before our eyes.

DON’T EXPECT JUSTICE

The treatment of blacklisted workers by the British legal system does not make us optimistic. The multinational corporations that ruined so many lives were literally able to buy themselves out of a High Court trial involving over 700 claimants.

Blacklisted workers do not expect justice from the State investigating itself. Blacklisted workers are participating in the slim hope that some evidence of the anti-union bias, institutional racism, and institutional sexism of the British State’s spying machinery will be exposed.

Keeping this dark underbelly of anti-democratic political policing hidden is against the public interest. It only helps the perpetrators, not the survivors, nor the British public.

The police can claim all they like that they were protecting democracy. But by spying on trade union members and colluding with our blacklisting, spycops are actually just protecting big business and capitalism.

For the avoidance of all doubt: capitalism and democracy are not the same thing.

Witness hearings procedural meeting

The Inquiry then held a meeting of four of the barristers representing core participants, in the hope of agreeing a format for asking questions of witnesses.

All this revolves around the “Rule 10” issue, referring to legislation setting out guidance for how a public inquiry should work. Rule 10 is not permission to ask questions of a witness, but the right to submit them to the Inquiry to have them asked. There is no requirement for the Inquiry to accept those questions to be asked, or to let a non-Inquiry barrister ask the questions – that is all at the discretion of the Inquiry’s Chair.

At the moment, the various lawyers submit their lists of questions to one barrister, the ‘Counsel for the Inquiry’, who then deals with the witness. The idea is that this stops it turning into an ‘adversarial process’ that feels like a criminal trial, with witnesses trying not to be ‘caught out’. It means placing a lot of trust in the impartiality, thoroughness and skill of the Inquiry Counsel.

Over the last week, the barristers for some of the different categories of core participants have been submitting the questions they would like to have asked alongside those being asked by the Inquiry. Some of our questions have been accepted by the Inquiry and asked. This has allowed us to unpick some of the points that matter most to us.

NO FURTHER QUESTIONS

However, there has been an issue with this system. Once a question has elicited an answer, it has not been possible to follow up with another question. We have said all along that our input at this stage would be necessary for the effective examination of witnesses’ evidence. Another issue is the Inquiry’s reluctance to accept questions about the wider issues, such as institutional sexism, rather than about specific ‘facts’, as if the Inquiry is buying the police line that the past is a different country.

Last week, the Inquiry allowed two of the barristers representing non-state core participants to ask questions of witnesses. However, the request to do this from one of those barristers, by Rajiv Menon QC, led to Mittings’ extraordinarily fractious behaviour.

Specifically, SDS undercover and administrator Joan Hillier was asked about the possibility that her close colleague, Helen Crampton, had deceived someone she was spying on into a relationship. The Chair, Sir John Mitting, felt that this question was sprung on Hillier without warning and was therefore not fair.

THRASHING IT OUT

The meeting today included Menon, with Ruth Brander (also working for the non-state core participants), Oliver Sanders QC (representing 114 undercover officers), and Peter Skelton QC (from the Metropolitan Police).

Mitting began by saying that the format for questioning witnesses remains a ‘work in progress’. There will be a meeting in January for those involved, to discuss how it will work for the next round of hearings. These are currently scheduled to take place in March or April 2021.

All four lawyers said that was fine with them.

Mitting said to Menon that Rule 10 is there to allow the Inquiry to control its proceedings. He listed three incidents that he wanted to give Menon a dressing-down for:

1. Tariq Ali, answering a question of Menon’s, had named an individual, breaching a Restriction Order on divulging the name.

“This isn’t a court”, said Mitting. We can’t explore every relevant issue, we have statutory limits. I have to protect people’s rights and privacy.

2. Menon’s question to spycop John Graham (about taking part in a ballot at a political meeting that he had infiltrated) was described by Mitting as ‘unhelpful’. He agreed it did not cause any harm, but he still didn’t like it.

3. Mitting felt that Menon questioning former officer Joan Hillier about her colleague Helen Crampton (who may have had a relationship with someone she was spying on in the Vietnam Solidarity Campaign, George Cochrane) was bang out of order.

Mitting said witnesses must have significant advance warning of what they’ll be asked about. We can’t let you do this stuff, it’s not a trial, we have different processes than a court.

MENON NAMES NAMES

Menon said that Ali was asked by the Inquiry about a meeting at the Notting Hill branch of the Vietnam Solidarity Campaign. A spycops’ report was on the screen, with a redacted name of someone who’d distributed a leaflet. Ali couldn’t comment without knowing the name.

Rajiv Menon QC

Menon explained that he knew the name. He believed the man to be dead and so unaffected by privacy issues, and hoped that telling Ali the name would help jog his memory. Which, indeed, it did.

It turns out the man in question is not dead. Menon said if he’d known that he wouldn’t have named him, and he apologised. It was also this incident which led him to be more vague when questioning Joan Hillier later on.

Menon emphasised that these mistakes are the inevitable result of having to process thousands of pages of police documents in a short space of time, check the facts and formulate questions. They received 5,500 pages with only four weeks to go before the hearings began.

MENON DE-VOTED

Menon then turned to his questioning of officer John Graham, defending it stoutly. Graham was one of nine undercover officers present at a meeting that voted on the route of a demonstration. Menon said it was directly relevant to the Inquiry, not because the nine might have swung the decision one way or the other, but because we should be told how the police voted.

If, say, they voted with the people wanting a confrontational route, then it’s directly in the Inquiry’s remit – it’s about spycops and public order policing. Either way voting at all is contrary to Special Demonstration Squad founder Conrad Dixon’s document on the ‘penetration’ of groups, which insists they eschew active roles.

Mitting admitted that “no harm whatever had been done by that line of questioning”, and that his doubts about its usefulness were just a “matter of opinion” between him and Menon.

MENON & THE FIRST SPYCOP RELATIONSHIP

Menon then addressed his questioning of Joan Hillier. The issue of officers deceiving people they spied on into relationships is a major theme of the Inquiry, and here we have a strong indication that it was happening from the start. He said Hillier is the only surviving officer who infiltrated the group (Notting Hill branch of the Vietnam Solidarity Campaign), so he would be failing in his professional duty both to his clients and to the Inquiry’s seeking the truth if he didn’t ask questions of the only possible witness.

Menon said he only got the information the night before. He drafted specific questions (albeit without sources) and sent them to the Inquiry lawyers, but they didn’t bother getting back to him. When Counsel to the Inquiry failed to ask about this, he applied to ask these questions himself. At the time, Mitting agreed that this was an important issue, and gave permission for the questions to go ahead, so it’s a bit rich to complain.

Menon stands by his decision to raise this issue, and has suggested that better communication on the Inquiry’s part might prevent problems of this kind arising again.

Mitting said that the outside world doesn’t understand the Covid-times problems of getting documents to everyone who needs them. He recognises that it puts a lot of time pressure on lawyers, but that’s going to be the way it is.

Menon asked if documents could be handed out piecemeal, as soon as they’re redacted and whatever, rather than piling them up and dropping them in a massive stack at short notice. He wants maximum time with as much of the evidence as possible. He requested that materials for the next hearings are made available sooner rather than later (eg in December rather than February), to him and the other non-state lawyers, so they have time to go through the evidence in advance of the next set of hearings.

BRANDER: GIVE US TIME

Ruth Brander (also representing non-state core participants) said it would help to have a proper explanation about exactly what the Inquiry’s delays are. Victims of spycops feel like they’re at the bottom of the list for their input, the last to get the disclosed files, and left with explanations.

Ruth Brander

She said non-state core participants will be able to give real value to the understanding of documents yet they don’t get to see them until they’re made public, after they’ve been brought up as evidence in the Inquiry. It makes her clients feel repeatedly excluded from the Inquiry. (Non state core participants have repeatedly raised this issue with the Inquiry Legal Team, but been consistently ignored. It is seen as another way in which the Inquiry is skewed in favour of the police, who obviously have access to the files that they themselves made.)

Brander pointed out that if the non-state core participants only see the material “for the first time, as it’s passing by their eyes on the screen, they have virtually no opportunity to feed into the process”,

Mitting said that he asks for questions for witnesses to be handed in a week in advance, and they generally do get asked, so what’s the problem?

Brander said both she and Menon struggle with the seven-day deadline because she’s not allowed to share the disclosed police documents with most of her clients. For most, they first see the evidence as it rolls by on the screen during the hearing. At the end of each day, she receives queries from her clients wondering why certain questions weren’t asked.

Especially, the women deceived into relationships want to know about the origins of the practice, but aren’t allowed to see documents unless they relate to the period that the particular officer was involved in.

BRANDER: EVIDENCE ALREADY SHOWS WE NEED ACCESS

Brander noted that we’ve had two officers this week who admitted going out for dinner and drinks with women they spied on very early in the history of the spycops units, and that they did it to bolster their credibility. This is important and relevant to the women later abused by officers, but they don’t get to suggest questions because they don’t see the material in advance.

Brander made a solid proposal, asking for the remainder of this phase – namely this week – to have ten minutes at the end of witnesses’ evidence for non-state questioning. This will allow her to communicate with clients who’ve come up with questions while following the hearing. She emphasised that this would assist the Chair in his role, not just be some kind of ‘favour’ to her.

She then said she wants to broaden the scope of questioning, not keep it limited to people directly affected by that individual witness. The women deceived into relationships have a lot of knowledge and expertise that others can’t bring to bear on this. Black justice campaigns and others will be in a similar expert position to see the systemic issues and ask the right questions of the witnesses to reveal the over-arching themes.

POLICE LAWYERS

Skelton represents the Metropolitan Police. This is the organisation which tried to strike out court cases brought against them by the women, and caused years of delay to this Inquiry, by applying for every officer to be given total anonymity and every hearing to be conducted in private).

He said ‘the Met hasn’t improperly delayed the disclosure process’. He added that he knew Menon didn’t believe him but his clients hope that the Inquiry does.

That out of the way, Skelton said that Menon’s questioning of Hillier was an ‘issue of fairness’ and suggested that such contentious issues need more consideration. Hillier should have been told she’d be asked about Helen Crampton’s alleged relationship, and seen the evidence if it exists. This can’t be allowed to happen again.

Skelton said the Inquiry is inquisitorial not adversarial, it’s not trying to build a case. Rule 10, under which witnesses are questioned by a single lawyer working for the Inquiry, encourages witnesses to give ‘free and open evidence’ because they feel the questioner is neutral, not hostile. He took the trouble to specify that this was especially important for elderly witnesses like these, who have felt ‘personally under attack’ for many years

Skelton concluded by saying that everyone wants to see their questions asked, but that would have to apply to everyone and would be long-winded and unwieldy (and costly). The Met are satisfied with the current, ‘hybrid’ arrangement, and would like Mitting only to allow extra questions when there are ‘significant factual disputes’.

Sanders, representing a lot of individual officers (including HN328 and HN336), endorsed Skelton’s words. And criticised Menon for asking questions of HN328 last week without Mitting’s express permission. Police witnesses aren’t alleged to have done anything wrong, he said, referring to the subjects of an Inquiry into the wrong-doing of police officers. It unsettles them to be asked things they didn’t expect. Some of the non-state core participants have partisan and hostile views about the officers, he said. The police hate the idea of the non-state legal representatives getting ten minutes to effectively cross-examine them.

David Barr (Counsel to the Inquiry) said Rule 10 avoids delay and repetition, makes it fairer and keeps costs down. It’s more work for lawyers, certainly, but basically worth it.

Mitting said he’d discuss this issue with Barr and get back to everyone.

MITTING: FEELING BETRAYED

Before the break, Brander brought up another issue. The system of suggesting questions in advance cannot work when her clients who would have questions to suggest don’t see the evidence in advance. Either they need access to the evidence in advance, or else they have to be allowed to ask questions at the end. To have neither is “have both hands tied together behind our backs” and shuts us out.

Mitting then made a really insensitive criticism of ‘Rosa‘, one of the women who was deceived into a relationship by spycop Jim Boyling. Mitting said that multiple core participants have asked for a live-stream to their homes, like Mitting has to his. He has only granted this request to one person, ‘Rosa’, because of her exceptional circumstances. When she applied , she said she didn’t want these circumstances to be made public.

Mitting said he was surprised that Phillippa Kaufmann QC’s opening statement last week included a detailed description of Rosa’s story and circumstances, using a lot of the same phrasing that she’d previously wanted kept confidential.

Brander seemed taken aback, unsure of the exact basis of Mitting’s complaint. It wasn’t relevant to the question of seeing evidence in advance, it was more like venting something that had been bothering him for a while. His tone firmly indicated a sense of having been hoodwinked in some way.

Brander said she’d try to speak to Rosa but could certainly affirm that there is no doubt to the truth of Rosa’s statement. Rather it appears she decided it was OK to mention her circumstances in public in the specific context of Kaufmann talking about exactly what spycops did to women they abused.

PROCEDURE DECISION

The Inquiry took a break for Mitting and Barr to discuss the changes to the procedure of questioning witnesses. They came back with the decision that for the rest of this phase – i.e., until Thursday, with only two witnesses – once Counsel for the Inquiry has finished asking the aggregated questions from the various lawyers, the hearing will pause for 10 minutes and the lawyers can tell Mitting if they’ve anything additional to ask.

Mitting spelled out that there is no way this will be the format for the next hearings, but a better system will have been designed by then. Brander and Menon thanked him.

MITTING: ALOOF AND REMOTE

Brander raised Mitting’s querying of Rosa, saying Rosa wants to make a public response as:

‘she was quite alarmed that her integrity was called into question in a public hearing without advance notice’

As for the chronology, Brander explained, Rosa’s refusal to agree to her application being made public was a week before the Opening Statement was finalised, which included a lot of the same details. It was a very difficult and painful process for Rosa to feel she could put her story in a public Opening Statement made to the Inquiry. She took it right to the deadline because it was so unsettling for her.

Mitting said he accepted all that unreservedly, and that he never meant to criticise her integrity:

‘It’s not necessary, frankly, for her to make a public response, but she’d free to do so if she wishes’.

This is yet another example of his absolute failure to understand what he’s dealing with. He treated it as if Rosa had somehow got one over on him, or debased his precious gift of confidentiality. The fact that he brought it up in response to a request for live-streaming speaks volumes too; the subject was public streaming, yet he didn’t talk about that, but went off into something that appears to have stuck in his craw since last week and he can’t shake it.

His final comment, with the dismissively barbed ‘frankly’ jutting out, showed that he has no understanding of the scale of the trauma Rosa and the other women face. Nor, indeed, of the way that trauma in general produces conflicting intense feelings.

Many of those abused by spycops simultaneously feel that they want the world to know their story, but also that they’ve been invaded too much and can’t stand the pain of the slightest thing more being taken from them. When dealing with the huge trauma that comes from having your life violated by spycops, it is hugely important for victims to have some semblance of control over the narrative of their own lives.

Mitting showed more concern for his feeling put-out at having a decision seemingly undermined than for all the unspeakable horror that Rosa has been subjected to and her right to tell of it as she see fit, despite having had it explained to him so unflinchingly and eloquently by Phillippa Kaufmann QC.

COPS will be live-tweeting all the Inquiry hearings, and producing daily reports like this one for the blog. They will be indexed on our UCPI Public Inquiry page.

<<Previous UCPI Daily Report (16 Nov 2020)<<

>>Next UCPI Daily Report (18 Nov 2020)>>

2 comments on “UCPI Daily Report, 17 Nov 2020”