Jeremy Corbyn, MP spied on by the SDS

And still they come. The tide of revelations about the extent of spying by Britain’s political secret police is still flooding in.

When the scandal first broke four years ago, the breadth of groups spied on astonished us. It appeared that the units regarded any political activity outside the sliver of the spectrum represented in parliament as a threat. But we now know it was even broader than that.

In June last year we learned that the Green Party’s Jenny Jones had a file opened on her after she was elected to the Greater London Assembly, and it ran for at least eleven years. A fellow Green, councillor Ian Driver, was also spied on, with his file noting his support for such subversive terrorist causes as equal marriage.

Two weeks ago it went further with whistleblower Special Demonstration Squad officer Peter Francis naming ten MPs who he saw files on, including three that he personally spied on.

The list includes Tony Benn, Ken Livingstone, Dennis Skinner, Joan Ruddock, Peter Hain, Diane Abbott, Bernie Grant and Labour’s current deputy leader Harriet Harman.

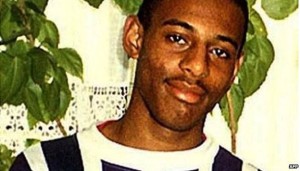

The two other targets have particular resonance. One is Jack Straw who, as Home Secretary, was ultimately in charge of the police. The other is Jeremy Corbyn who was spied on by Francis in the 1990s. Francis was deployed by his manager at the Special Demonstration Squad, Bob Lambert.

Protest against Bob Lambert’s employment at London Metropolitan University, March 2015

Ten years later Lambert was running the Muslim Contact Unit (quite why the intelligence-gathering Special Branch would send its most experienced infiltrators and spies into an outreach project is a question for another time).

Shortly after leaving the police he published a book on police efforts to deal with Muslim extremism in London. His parliamentary booklaunch was hosted by Jeremy Corbyn MP, the man Lambert had sent spies to watch, in September 2011, a month before Lambert was exposed by activists.

In a further twist, Lambert is now controversially employed as a lecturer at London Metropolitan University in Corbyn’s constituency of Islington North.

A furious Corbyn told this week’s Islington Tribune

I was interested in his book at the time and I was involved in the launch. But for all I know he could have had me under surveillance.

Like so many corrupt state officials around the world who’ve been caught and are facing an inquiry, Lambert’s memory has become conveniently selective. He does not deny tasking Francis to spy on Corbyn but says he can’t remember.

The MPs attended parliament the day after the revelations and had a forty minute debate (full transcript here). The Home Secretary wasn’t there, so the government spoke in the form of the Minister for Policing, Criminal Justice and Victims, Mike Penning.

The one bit of positive new information was the assurance that Peter Francis, and any other whistleblowers, will be given immunity under the Official Secrets Act at the public inquiry. It’s notable that the inquiry was singled out – the long standing threat against Francis and, by extension, others who speak elsewhere still stands, apparently.

Challenged on the sexual relationships that officers deceived women into, Penning said that

the Met police apologised

Perhaps he knows a different Met to the rest of us. The Met who deployed all the spies have only admitted that three out of an estimated 200 were actually police officers.

They are still spending huge amounts of public money resisting the plain, established truth in court. The partner of John Dines, Helen Steel, is back in court next month trying to get the Met to drop their absurd, insulting obstruction tactics.

Back in parliament, Jack Dromey made the bold claim that

Labour has for years pressed for much stronger oversight of undercover policing

This flies in the face of the fact that every one of the political police spy units was set up under Labour who, in the early 2000s, handed control of three of them to the Association of Chief Police Officers, a private company exempt from Freedom of Information legislation.

Peter Hain led the targeted MPs’ charge and was the first of several who demanded to see their full files. Penning steadfastly refused.

Penning did say more than once that there would be a release of whatever wasn’t needed to be redacted for reasons of security. One of the affected MPs, Joan Ruddock, immediately put in a request to the Met for her file. In the days that followed, the Speaker of the House of Commons John Bercow underlined the seriousness of the scandal. The following week Ruddock was told that the Met would ‘neither confirm nor deny’ that there was any file on her.

Penning did say more than once that there would be a release of whatever wasn’t needed to be redacted for reasons of security. One of the affected MPs, Joan Ruddock, immediately put in a request to the Met for her file. In the days that followed, the Speaker of the House of Commons John Bercow underlined the seriousness of the scandal. The following week Ruddock was told that the Met would ‘neither confirm nor deny’ that there was any file on her.

The MPs should certainly get to see the information that was collected about them, but they should not have it as a privilege. It is clearly established that the spy units were extraordinarily intrusive, with a paranoid vision of political activism and scant regard for the rights and wellbeing of citizens.

Most of the official reports such as Operation Herne are self-investigations and have thus been self-discrediting. We cannot trust the words of proven liars. Everyone who was spied on by these units should be told and given proper access to their file to judge for themselves what was recorded and why.